William M. Wood

William M. Wood’s earliest and later years went badly. In between, he was a Horatio Alger real-life success story, including marriage to the boss’s daughter. His immigrant parents came from the Azores (which Wood would come to cover up) to Martha’s Vineyard and then New Bedford, Massachusetts. By age twelve, Wood had been forced into the job market to support his recently widowed mother. His business skills were honed working for the New Bedford and Fall River Railroad Company during a portion of the 1870s. Then, during the early 1880s, he was practically adopted by a prominent Fall River cotton mill treasurer, who valued his young friend’s paymaster skills so much that Wood was invited to live at his home. As detailed by his biographer Edward J. Roddy, Wood’s career path ultimately led him to Lawrence, Massachusetts, where his vast Wood Mill became the core enterprise of the trust known as the American Woolen Company. Wood’s exemplary work ethic contributed over time to his becoming “the most important man in the woolen industry in the world." Always thinking large, Wood strove to duplicate his success by offering a buyout to Fall River mill stockholders preliminary to forming a Cotton Textile trust. The offer was rejected. Had it been successful, there would have been a fascinating clash and predictably fierce warfare with Fall River native and cotton industry kingpin, M.C.D. Borden.

William M. Wood’s earliest and later years went badly. In between, he was a Horatio Alger real-life success story, including marriage to the boss’s daughter. His immigrant parents came from the Azores (which Wood would come to cover up) to Martha’s Vineyard and then New Bedford, Massachusetts. By age twelve, Wood had been forced into the job market to support his recently widowed mother. His business skills were honed working for the New Bedford and Fall River Railroad Company during a portion of the 1870s. Then, during the early 1880s, he was practically adopted by a prominent Fall River cotton mill treasurer, who valued his young friend’s paymaster skills so much that Wood was invited to live at his home. As detailed by his biographer Edward J. Roddy, Wood’s career path ultimately led him to Lawrence, Massachusetts, where his vast Wood Mill became the core enterprise of the trust known as the American Woolen Company. Wood’s exemplary work ethic contributed over time to his becoming “the most important man in the woolen industry in the world." Always thinking large, Wood strove to duplicate his success by offering a buyout to Fall River mill stockholders preliminary to forming a Cotton Textile trust. The offer was rejected. Had it been successful, there would have been a fascinating clash and predictably fierce warfare with Fall River native and cotton industry kingpin, M.C.D. Borden.

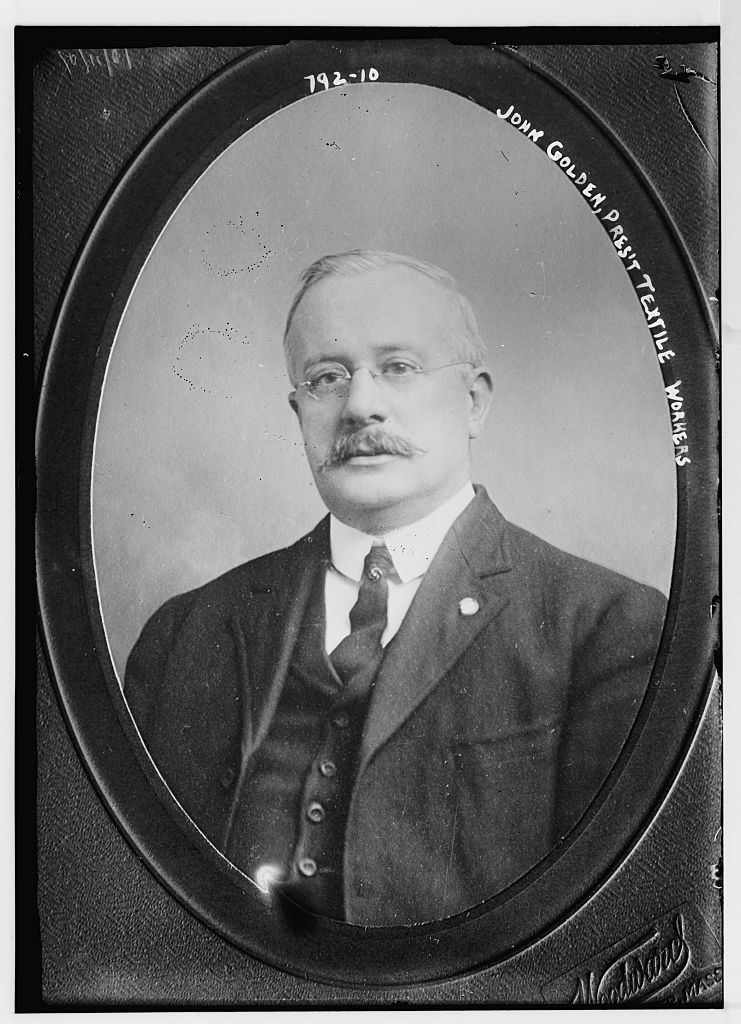

John Golden, President of the Textile Workers, Woodward, Massachusetts.

While the Bread and Roses strike of 1912 in Lawrence continues to generate intense scholarly interest, the writings generally reflect the fascination of labor historians inspired by a proletarian victory achieved under the auspices of the anti-capitalist IWW (Industrial Workers of the World, “Wobblies”). A rich array of primary source material has been used effectively by researchers in assisting them to explain how a disorganized and chaotic worker walkout became rationally organized and structurally sound. From among the anonymous immigrant dominated workforce emerged a newborn leadership that has endeared the strikers to gender and ethnic historians because daunting odds against success were overcome. The mesmerizing though transient IWW organizers who melded mill operative resistance loom larger than life for outmaneuvering the Lawrence establishment from beginning to end in a dramatic nine-week confrontation that began in January.

After that the story becomes anti-climatic – except when the potential second Salem witchcraft trial results that were projected by contemporary critics of the Massachusetts legal system were contradicted by the acquittal of jailed “radical” strike leaders Joseph Caruso, Joseph J. “Smiling Joe” Ettor, and Arturo Giovannetti at the conclusion of their court case in November 1912. The tumultuous celebration by thousands of jubilant greeters in behalf of the three released prisoners provided pro-labor historians with another positive event on which to focus. However, students of the Lawrence strike ruefully acknowledge that substantial damage to the worker cause had already occurred. The “No God, No Master” message associated with the IWW parade conducted on September 29 played into the hands of super patriots who could and did subsequently rally the people of Lawrence “For God and Country.” By 1913, it was as if a gale had passed through and swept the “alien” radicals away, depositing them in Paterson and elsewhere. Without staying power, the IWW had pretty much abandoned the militant minority of Lawrence whose collective voice of outrage was muted. Tales of triumphant success were often replaced by an uneasy sense that there had been something tainted and even shameful in striker conduct.

Why were the conservatives ultimately so successful when the nation had been aroused to anger over the social inequities at Lawrence in this Progressive Era year of the Bull Moose campaign and Gene Debs’ best run for President? Reformers had the upper hand in reporting on a substandard wage structure mandated by tariff-protected, profit-fattened corporations. Government investigations provided riveting testimony of the inferior economic existence of thousands forced to skimp by on less than just living wages. One consequence was the pathetic fate of the ill clad and undernourished children of Lawrence that disgusted a public attuned to child labor problems by the efforts of Lewis Hine and like-minded reformers. And didn’t the authorities have hearts of stone in their disposition to use excessive physical force in their policing capacity and in exercising little judicial restraint while meting out stiff fines and jail sentences? Who would not have been sensitized to the fate of mothers handled roughly by the interfering authorities as they sought to bid farewell to their children who they were sending by train to be cared for by humane supporters? Who would not have been moved to anger that a young man could be stabbed to death by a bayonet thrust into his back and that no one was held accountable?

The ephemeral nature of the IWW victory despite unprecedented public good will indicated that in the long run the Irish-dominated city government working in conjunction with influential Catholic pastor James T. O’Reilly would recapture control from dangerous “outsiders.” But during the strike period itself these Lawrence powerbrokers had welcomed a labor “outsider” who was in fact one of their own philosophically. The IWW was in a vise, being squeezed on one side by powerful capitalists as epitomized by Wood, chief spokesperson for mill management, and from the other side by John Golden, president of the United Textile Workers of America. Incensed by Golden’s conservatism, the IWW targeted this “labor faker” and created a negative caricature that has persisted over time. Golden is portrayed as a traitor every bit as willing to see the strike fail as management was, and wittingly or unwittingly as a compliant tool of management.

Strike leader Joseph Ettor did not welcome Golden’s appearance in Lawrence shortly after the strike was underway, proclaiming that the strikers would not have faith in Golden to arbitrate a settlement in conjunction with state or local government. Ettor was responding to a blistering speech delivered by Golden upon his arrival, in which he had denounced Ettor and his “outlaw organization” that dangerously fomented class hatred. Golden’s UTW Lawrence local contained skilled English-speaking loom fixers who became unemployed now that those in lesser mill occupations who had taken to the streets did not need their services. Back home in Golden’s Fall River, the Irish-Catholic owned Fall River Daily Globe, through editorials and slanted reporting, provided the perspective on events that would essentially represent the viewpoint of the UTW leader. Thus “A Deplorable Situation” existed in Lawrence marked by unlawful property destruction attributable to “misguided strikers” influenced by the “inflammatory appeals of irresponsible and glib-tongued trouble breeders.” The issue, then, was with the ethnic composition of the mill employees, so different, and in the newspaper’s estimation, so inferior to the old stock English, Irish, and French Canadians whose respect for law and order and good sense would never have allowed them to fall under the influence of agitators. The problem was that the southern and eastern Europeans were impulsive and “prone to be hot-headed and unreasonable.” Newspaper readers were titillated by reports that Governor Eugene N. Foss, a textile mill owner, was receiving protection on his daily walks supposedly because he had been targeted for Black Hand death threats.

Legendary Big Bill Haywood wasn’t about to tolerate such an attack on his followers, and verbally assaulted the UTW’s unwanted interference in a speech delivered at Fall River in early February as he reflected back on the first days of the Lawrence struggle. “It was a golden spectacle…. Trying to keep in with the capitalists; that is what Golden is doing and he is doing this at the expense of you people.” “John Golden and Bill Wood …. What a handsome pair. Golden, the head of the United Textile Workers, and Wood, the capitalistic thief. Golden has a fine way of settling a strike. He meets the manufacturer and says in that soft smooth way of his: ‘Well, now, can’t you and I just fix this little affair up all right.’ What he should do would be to demand that the operatives be given their rights….” Pursuing this theme, dynamic “Rebel Girl” Elizabeth Gurley Flynn told Polish immigrants that they must win this strike on their own. Using Golden as her foil, she told her audience that otherwise you might make the mistake of entrusting the task to Golden who would “take a trip to Boston and meet Billy Wood in the Hotel Touraine. Over a few bottles of wine, and some cigars [,] Wood would say, ‘Fifteen percent is too much.’ Golden would reply, ‘…I think so, too.’”

Even when AFL affiliates, operating through the Lawrence Central Labor Union, voted to strike at this very time, the IWW was not assuaged, suspecting that the purpose was to divide the labor movement. From jail, Ettor let it be known that the UTW was an enemy. From an IWW perspective the belated attempt to work out a separate solution without interacting with the IWW influenced Strike Committee represented a Benedict Arnold sellout. If and when management might become less intransigent about resisting striker demands, the AFL would, of course, become management’s choice to deal with. The IWW was resolved not to allow the few to swallow the valiant efforts of thousands who had resisted temptations to return to work. Golden and the UTW had used a proclamation to appeal to all workers to accept craft union guidance. In effect, the AFL was attempting to destroy a plausible victory by the masses that would certainly see through the ruse. National IWW organizer William Trautmann accurately predicted that this UTW proclamation asking strikers to reject Wobbly leadership would fall on deaf ears, and that such a proposal was so unrealistic that it must have been formulated “in brains of idiots.” Furthermore, by way of proof that Golden was a dupe of management, the IWW publicized that AFL textile unionists had in the past been sent to work as “scabs” by Golden during a strike in Maine.

Golden’s attempt to end the strike exclusively through craft union arrangements aroused the wrath of the IWW, leading to creative denunciations. As noted by historian Bruce Watson, a means to solidarity among the large ethnic mix came through training people at strike rallies to loudly denounce “John Golden” whenever his name was mentioned.

The thousands of rank and file who held out for more had plenty of opportunity to vent their hostility upon learning that Golden was in Lawrence urging his membership to accept a five percent wage advance proposal offered by William Wood at the beginning of March. They could also reflect back upon their attempt to evoke public sympathy and reduce family costs by sending the children out of Lawrence and remember that Golden had been the foremost critic of this “desperate” strategy designed as part of the IWW’s “anarchistic propaganda.”

Golden could give as good as he got (in his estimation, Wobblies were “wild-eyed inflammatory demagogues”), and a Washington Congressional hearing room far removed from the tumult of Lawrence did not have a calming influence on his perspective about the Lawrence “revolution.” The Lawrence owners like Wood had brought their troubles upon themselves (for once he would have agreed with songwriter Wobbly Joe Hill in the condemnation of “wooden-headed Wood”). The recent trouble had as its root cause the purposeful enticement of foreigners by Lawrence management over the previous decade that had changed the city in a deleterious way. The Congress could best react to this example of greed by restricting immigration. Golden pointed out that no English-speaking workers had initially gone on strike against lower pay that accompanied the Massachusetts law reducing millwork to a fifty-four hour maximum that had gone into effect beginning in January. Radicals had used weapons in forcing others from their machinery. While acknowledging the penuriousness of management and that pay should be higher, the means employed in seeking redress had been disgraceful. Golden took full opportunity to attack one of his arch enemies by insisting that Ettor had openly preached violence, a claim that Lawrence strikers in the conference room vigorously denied. How was it, then, came a logical inquiry, that the more responsible UTW had not won over the strikers? Golden retorted, “Your Ettors and your Haywoods, who have gone down there and poisoned the minds” and have made me into a “monster” in the eyes of IWW controlled strikers.

Back from Washington, Golden would debate with the editor of a textile journal, Fibre and Fabric, and blame Wood and other similar capitalists for lacking wisdom in having made Lawrence the most difficult community to organize prior to the recent troubles and insist that the mill barons were now paying the price for their blind obstinacy. But it was also apparent that management was about to pay a better price for labor in excess of their original offer to end the strike. Now Golden insisted that the UTW was responsible for the impending positive outcome, and openly suggested that the Commonwealth’s Attorney General would investigate what the IWW had done with financial donations, strongly intimating that chicanery would be uncovered. This would serve the IWW right, for their letters signified “I Want War.”

One of the national commentators who studied this conflict was horrified by the elitist stance of Golden and contrasted his attitude with the enormous compassion of the IWW toward the unskilled ethnics. Golden didn’t see it that way, insisting that the UTW efforts were in behalf of the “poor people. We have no apologies to make, we don’t care where criticism comes from….”

The criticism continued to come from contemporaries, as it has from later scholars, one of whom suggests that Samuel Gompers followed upon Golden by offering testimony at the Congressional hearing that was supposed to corroborate Golden’s statements. In fact, according to this interpretation, Gompers was attempting to moderate some of the exaggerated remarks of his colleague about the IWW leaders as well as their faithful Lawrence recent immigrant supporters that many Progressive critics would not have taken to kindly. Golden had callously demonstrated little sympathy for those who had been brutalized by the police while attempting to exercise their right to send children to safer havens. On the other hand, Gompers commended Golden for promoting the interests of all textile workers: “There is no man in all the country more self-sacrificing and more honest and altruistic in his efforts to help the working people….”

Students of labor history are also convinced that the worker victory at Lawrence had not been abetted by John Golden’s involvement (though Golden continued to claim otherwise), agreeing with the contemporary winners who were determined to cleverly provide reminders that the role of their UTW rival had, at best, been inconsequential (especially because Golden maintained after the strike that the IWW leaders at Lawrence had misspent donations, living “lavishly” and “in riotous debauchery.”) Joe Hill did so through musical composition (“A Little Talk With Golden”), while the IWW treasury that was the object of Golden’s suspicion had enough in it to subsidize publication of a book entitled: “What John Golden Has Done for the Workers of Lawrence” that was filled with blank pages!

There is a disconnection between Golden at Lawrence and Golden whose roots were in the textile union center of Fall River. Golden’s philosophy and his strong will need better understanding if we are to get beyond treating him simply as a hopeless obstructionist who became an object of ridicule to IWW propagandists.

Golden, a native of Mossley, Lancashire, became self-educated by disciplining himself to read after spending long days in cotton mills from the time he was ten years old, working as a doffer and backboy. Before emigrating to Boston and then directly to Fall River, Golden had been exposed to labor conflict, endured the sting of the blacklist, and had become a committed unionist. He went on to organize the Piecers’, Doffers’, and Backboys’ Union of Fall River and served as its treasurer for several years. From the time he was of sufficient age and was given two mules to operate, Golden became active in the Fall River Mule Spinners Union. His commitment and notable organizational skills then led to involvement with the National Mule Spinners organization of the United States and Canada, in behalf of which he again assumed fiscal duties as treasurer. This elite craft status organization served as the springboard to executive leadership of the UTW.

His craft skill and his decision to settle in the “Manchester of America” molded John Golden. Both factors are essential for an understanding of why he was motivated to act the way he did during his UTW tenure.

Two of our ablest social historians have written of the Fall River area’s textile heritage. Referencing their terms “Constant Turmoil” and “The Fall River System of Unionism” helps bring into focus the controversy–filled history of the Spindle City, dominated on labor’s side by the organized mule spinners. For a generation, beginning in 1848, the emerging textile colossus would suffer economic slowdowns in production during a half dozen enormously divisive conflicts between labor and capital. During all of these struggles, worker militancy, inspired by a strong sense of self-worth, emanated not from the native born but from English and Irish residents who had arrived with a belief in worker organization.

Workers fought valiantly throughout the 1870s, scoring a notable though temporary victory in 1875, and demonstrated impressive ability to show strength in numbers at park protest rallies and by conducting a monster protest parade that focused on the malfeasance of mill officers and directors. Social critics such as visitors Albert Parsons and the demagogic Denis Kearney would have had every reason to compliment militant anti-capitalist critics who were guided by socialist newspapers, the Labor Journal and the (Fall River) Labor Standard.

In 1880 the socialist Labor Standard editor’s political defeat in a failed effort to become a state representative signaled that the city had passed through the most radical phase of its history. The voters had decisively chosen a more conservative candidate from the ranks of labor to serve as their state representative.

Winning candidate Robert Howard was secretary of the local mule spinners. These were elite, all male craftsmen from Lancashire who brought their talent and a strong commitment to unionism with them. Using his organization as a base of power, the popular spinner secretary now became a powerhouse in the local Democratic Party that was dominated by his Roman Catholic co-religionists. In the mid-1880s Howard was elevated to a state senator. He would use his position into the 1890s promoting labor legislation that would help identify Massachusetts as a labor reform state. By then he had, prior to resigning, reigned as Grand Master Workman of the Knights of Labor (KOL) of Massachusetts that possessed the largest state membership of this first meaningful national worker organization. But his most comfortable association would be with Samuel Gompers, a connection that began when they befriended one another and worked cooperatively as delegates to the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada, an alliance that carried forward with this first organization’s metamorphoses into the American Federation of Labor.

First and foremost, Howard the trade unionist aspired to bury the previous rancor. This was easier said than done, especially when local mill management was less motivated than he in seeking industrial peace with justice for all. Howard must have wondered about his approach when management unreasonably brought on a strike in 1884, aggressively imported strikebreakers, used the blacklist, and were able “to starve us into submission.” Though management prevailed, it had taken eighteen weeks to do so. For this had been a mule spinners’ strike, and these proud workers had shown their mettle.

Within a very short time, management was more ready to buy into the “business unionism” approach to labor negotiations. Howard and his co-unionists took seriously their “Defence, not defiance” motto and had proven they would resist, and resist hard, should management pursue its unilateral decision making about wages, machinery speed, and other work conditions.

Through its Cotton Manufacturers’ Board of Trade, the city’s mill capitalists acknowledged the unique strength of the mule spinners, who had the capacity to tie up production, by granting formal and exclusive recognition of the union in late 1886 while also agreeing to sit down and “arbitrate” (negotiate) wage matters with spinner officers. Howard’s strategy of appealing to management by presenting as a conservative, responsible body willing to carefully study raw cotton purchasing costs and finished cloth sale prices, as well as the complexity of working different quality material, as the basis for reaching mutually acceptable wage scales, had finally found acceptance. The willingness of a very high percentage of these craftsmen to commit to unionization and a dues structure that enabled Howard to publicize that on a per capita basis his union was the richest in the country would have the desired effect of giving management pause about inciting any more confrontations. At the same time, management could be confident that Howard would control any firebrands within his organization.

Howard’s fondest wish was that other cotton mill workers would take their cue from his union and organize. On three occasions management would offer special wage concessions to the mule spinners only, which should have served as an object lesson. In reality it sometimes inspired jealousy and even a demand that the mule spinners hold out until all workers received spinner level benefits. This is when Howard’s reaction would demonstrate why his union had separated out of the industrial unionist KOL that welcomed all who toiled in favor of the AFL and Gompers’ craft centered business unionism. Though Howard explained that he was not hard-hearted, and that many mule spinners came from multiple mill worker households and would like all workers to fare well, the bottom line was self-help. Howard’s perspective was that it was difficult enough defending spinner interests without assuming the impossible task of assisting thousands of unorganized and mostly unskilled or semi-skilled operatives.

By the turn of the century, Howard’s admonition had been taken seriously and four other unions were the nucleus in forming the United Textile Workers of America in 1901. Loom fixers, carders, slasher tenders, and the numerically preponderant weavers formed this organization.

In a weak union industry, Fall River was by far the best example of labor solidarity. By 1904, about one in five Spindle City mill workers had followed Bob Howard’s advice to organize, making up approximately one half of 10,500 textile worker unionists in a nationwide industry with 300,000 employees.

Bob Howard would have taken some satisfaction in his hometown accomplishments, but he did not get to participate in the birth of the UTW, having suddenly experienced poor health in 1897 and enduring a poor quality of life before death took him at age fifty-seven in April 1902.

One of the people honoring his memory was John Golden, who in many ways had benefited from Howard’s mentoring and who had absorbed his predecessor’s philosophy and principles. Like Howard, Golden inspired loyalty and exercised strong leadership, though with less charm and with more of a confrontational personality. Associates often spoke of Howard’s brilliance and expertise, and the fact that Golden served side by side as a mule spinner officer meant that he had Howard’s respect and was able to learn from the master.

Both men experienced an element of doubt about the wisdom of working cooperatively with mill capitalists through business unionism. The unanswerable but gnawing question was whether the mule spinners settled for too little, i.e., mere recognition as a bargaining table equal, and had not been sufficiently aggressive in demanding higher wages when at their zenith of power.

The passage of time worked against the mule spinners, like anemia slowly sapping bodily strength. The mule spinning frame was threatened by technological obsolescence. By the 1870s the effective development of ring spinning frames had the potential to reduce mill operation costs because the latter style of frames did not require skilled operatives. Initially the Fall River mule spinners were protected by the fact that the mules spun a higher quality of yarn and because the machine life of expensive mules was about a quarter of a century. Since most of the mules had been purchased and installed by Fall River management during a boom period of building in the early 1870s prior to the depression of 1873, it wasn’t cost effective to replace them until they had outlived their usefulness, which they had as the mid-1890s approached.

The mule spinner rank and file ignored this unhappy reality and in unbridled fashion broke away from their executive leaders to initiate an 1894 strike in response to wage reductions now that the city was caught in the depressed national business cycle that had begun to have an adverse impact on business the previous year. Management reverted to an intransigent attitude that Howard and Golden had hoped was behind them, and not only prevailed but rubbed salt into the wound by accelerating ring spinning machinery substitution.

Howard’s only solace was that four unions tenaciously survived the ordeal, and that workers in these other specialties had finally succeeded in following the mule spinner lead. Furthermore, they were interacting cooperatively through a Textile Amalgamation. Of particular note was the emergence of James Tansey as the president of the card room employees. Tansey was destined to become the best known and respected labor official in twentieth century Fall River, as successor to Golden. From the mid-90s moving forward Tansey would for the most part help Golden (though jurisdictional disputes would lead them into separate organizational affiliations by the time of Golden’s death). Golden faithfully sought to emulate Howard by centralizing control and demanding a higher dues structure so that the UTW would operate from a position of strength as his now faltering spinners union had once done. Some of the other Fall River-New Bedford unions could not or would not comply.

Among the organized workers only the skilled loom fixers enjoyed wage remuneration equivalent to the mule spinners. The other workers willing to unionize, particularly the female carders, were not so fortunate. What the UTW was doing was reaching beyond its traditional craft elitism and conducting organizing drives that blurred level of skill distinctions. Having always preached that other workers needed to emulate the mule spinner example, the craftsmen would now reach down and lift up their textile brethren.

One can debate whether this was a logical extension based on idealism, or a practical move based on the realization that the mule spinner strength through splendid isolation no longer sufficed to protect workers. But there was no turning back, and the UTW outreach was impressive by the standards within the industry. As Golden would proudly advertise, 1912 was a very good year in his home city, for management not only conceded the same benefits procured at Lawrence, but without the need for a strike with lost wages. Also, despite the fissure with some of the other locals, the UTW succeeded in swelling its ranks by more than 5,000 during the year, helping total membership to rise to 16,500.

The most remarkable example of this transformation was when ring spinners were welcomed, and their specialty was incorporated into a new union title. Except for author William Hartford, this evolution has gone pretty much unrecognized, especially by historians who want to make the distinction between the commendable IWW’s universal embracing of Lawrence’s unskilled versus the supposed disinterest toward the masses by a disdainful UTW. In reality, the UTW was sending recruiting agents throughout the north and attracting a mix of textile operatives. Their real problem, as exemplified by information that the UTW had only 208 loom fixer Lawrence affiliates on the eve of the 1912 strike, was that management’s mode of operation in that community was as adamantly anti-union as Fall River’s had been prior to 1886. Potential recruits from among the mill workforce were intimidated or had adopted the attitude that paying union dues would be a waste of money.

It would seem, however, that ethnicity did matter to Fall River’s union officials, and that their pragmatic outreach to the lesser skilled was tainted by inherent prejudices that workers of Lawrence would sense was absent from the IWW organizers who treated them as true equals and galvanized them into action on a shared mission basis. Fall River had a long tradition of ethnic divisiveness and a clearly defined pecking order based upon duration of settlement, language, and experience in textiles prior to arrival. Here the advantage rested with the English-speaking émigrés from the British Isles who dominated skilled positions and launched the early union movement. Later there developed a strong rivalry when newcomers from French Canada became numerically preponderant. The mutual antagonism left the French feeling ostracized from the better mill jobs by English-speaking supervisors and excluded from union membership by the skilled mill workers. With the hard-pressed unions fighting for survival in the 1870s and early 1880s, the French Canadians were considered another tool of management willing to work for sub par wages. Even worse, they were “scabs” whose strikebreaking proclivities were encouraged by a French-Canadian pastor whose dominance over his flock was at least the equivalent to Pastor O’Reilly’s in Lawrence.

The universality of the Catholic Church, in theory, was nowhere to be seen in practice. A delegation of Irish spinners presented complaints to a sympathetic bishop who was a native of Ireland. Tension over workplace issues was the underpinning that spilled over into intense competition between the assimilationist bishop and the la survivance pastor that led to the placing of Notre Dame Church under interdict as the most dramatic part of a conflict ultimately requiring intervention by the Vatican. When a compromise solution was achieved in 1887 the visceral animosities began to subside, at least openly, but damaged relations had been institutionalized. The Irish Catholic Globe had hardly distinguished itself with outrageously slanted and vituperative reporting that had driven the French community into creating their own French language newspaper with which to respond in kind. John Golden’s funeral mass took place at Immaculate Conception Church in 1921, an edifice that was a stone’s throw from Notre Dame. Many of those in attendance would have been cognizant that the Irish minority in the eastern section of the city had been given sanctuary with the creation of Immaculate Conception parish, allowing them to “escape” from their original affiliation with Notre Dame.

While textile historians have debated the extent of militancy or passivity within the Franco work communities of Fall River and other New England mill towns, there is agreement that, with the passage of a generation, barriers had come down. By the 1910s Irish and English union leaders were pleased to add Franco-American names to membership roles and to publicly praise this group for steadfast commitment to worker rights.

The massive influx of new immigrants into the constantly growing mill complexes of Fall River became the new issue of concern for the unionists. It was as if the 1870s was being duplicated. Southern and eastern Europeans were arriving without English speaking skills or experience in textile work. After all the effort to win over the French it was disconcerting to witness history repeating itself. What should the unions do in the face of this newest challenge?

William Hartford provides a sound analysis when he writes that Golden worried about the new immigrants of Lawrence being susceptible to the 1912 radical message of the IWW that workers were destined to overthrow capitalism and gain complete control of their industrial destiny. Golden was probably as unprepared as Wood and the other Lawrence manufacturers to deal with this reality when he arrived at Lawrence. His worries about characteristics of the new immigrants did not, until that moment, include the thought that there was a strong radical component. To Golden the most endearing attribute of the most recent element of the Fall River workforce was a deeply imbedded conservatism and devotion to teachings of the Catholic Church.

Golden had uncharacteristically sounded as radical as an IWW spokesperson in allowing himself to be quoted that it was “nearly time that we pulled the lid off” when Spindle City management returned to former ways one more time and precipitated a strike in 1904. The altercation lasted for a half year and turned into a lesson in futility for the workers when a state government-imposed resolution of the strike in January 1905 resulted in no gains for more than 20,000 workers. There had never been such widespread suffering in the city’s history. Ultimately, as many as thirteen thousand residents would abandon the city and that exodus had a devastating psychological impact on those left behind. The previous population spiral was broken, sapping some of the exciting mindset that Fall River was a place to be, a vital industrial community. Instead, it became a center of misery, where the unemployed were reduced to scrounging for sustenance by berry picking and digging for clams that would likely be contaminated by pollution. The bitter memory associated with this failed effort must have been an additional factor explaining Golden’s attitude at the beginning of the Lawrence dispute eight years later. Even under stable union leadership workers had suffered incalculable deprivation. The realization that hundreds of French Canadians decided that their only recourse was to survive by returning to Quebec farms must have caused Golden to reflect on his own difficult escape from English poverty. Golden could well conjecture that Lawrence workers would find themselves in an unnecessary similar situation, brought on by irresponsible agitators who would ultimately abandon them to their suffering.

Golden certainly entertained mixed thoughts about the “new” ethnics. There was a strain of superiority that made him comfortable with the restrictionist advocacy of Bob Howard’s old friend Gompers and the AFL. Also, he was a product of a hierarchical mentality as a Roman Catholic in a community dominated by the local clergy. Roman Catholics were at least seventy percent of the population, with some estimates as high as eighty-five percent. The Irish were secure in their social status leadership, and the newcomers were more subservient and less willing to challenge the religious power structure than the French had been. The Irish dominance extended to labor union executive positions and within the local Democratic Party that had elected Irish mayors and was gaining control of the school committee at the time of the Bread and Roses strike.

But Golden was no hardliner bigot, going out of his way to inform a newspaper reporter how delighted he was that Portuguese, Polish, and other recent hires had stood by the unions during the “Great Strike” even though they didn’t have the financial resources of their more skilled mill brethren. They had also contributed to the “respectability” of the labor movement so cherished by Golden by responding to union admonitions about preserving the peace. The remarkable quiet was proudly advertised by Golden, particularly the fact that there were fewer arrests during the 1904 conflict than for a similar time period a year earlier. These developments influenced Golden to promote the industrial union approach that cost him some allegiance among skilled unionists who had not evolved into becoming more inclusive.

Golden’s crusade was directed against those other supposed “friends” of workers who would endanger souls, and here he had the total support of the Irish-American community. The influence of the Catholic Church on Golden and the other Catholic textile union executives cannot be overestimated. The Globe reflected the role of the Church in all facets of everyday community life in its selection of front-page news coverage. The only events of 1912 besides the World Series success of the Boston Red Sox (featuring a starring role by Hugh Bedient, who had formerly pitched at the Bedford Street grounds for the Fall River team in the New England League) that would displace news out of Lawrence would be detailed accounts of the return from abroad to the United States of two Cardinals of the Church. In conjunction with this editorial decision that piety sold newspapers, the speaking appearance in Fall River of convert David Goldstein, sponsored by two of the city’s Irish dominated Catholic organizations, merited extravagantly detailed review. Readers were given practically a word-by-word account by the author of Socialism: The Nation of Fatherless Children of how atheists were working to destroy Christian civilization by attacking church as well as family through free love advocacy.

If proof was needed that family values were under assault, the Globe provided evidence by printing that there had even been a red flag flying outside a building entrance attracting undesirables to a meeting dedicated to protesting the previous message of “apostate Socialist” Goldstein of the “lying brain and …black heart.” “Profanity a Feature of Last Evening’s Meeting” blazed a Globe headline in informing its presumably unsurprised readers that some of the socialist orators had no sense of propriety or decency as they delivered vulgar remarks, unrestrained even by the presence of women in the audience, directed at Goldstein and John Golden. The Globe editorialist insisted that this disgustingly immoral abuse of the right to free speech would necessitate a police presence to prevent potential duplication at any future socialist rally.

Secretary Joseph Jackson of the Slasher Tenders Union, which since the mid-1890s had gained a reputation as, by far, the most radical of the Fall River unions, had chaired this controversial meeting. At that time Jackson had earned the enmity of mill management and had divorced himself from other union officials by accusing the head of the weavers’ union of accepting bribery from the owners to keep his people quiet. Animosities continued to be fueled when management singled out slasher tenders for discriminatory punishment in the wake of the “Great Strike” and Jackson had no support system from the other unions as he did his best to fight back in behalf of his men.

By reminding his socialist audience of Golden the immigrant’s hypocrisy in blaming foreigners for the troubles at Lawrence, and in supporting immigration restriction, when he himself “has the stink of the steerage with him yet”, it is safe to say that Jackson wasn’t expecting any sudden support from his fellow unionist. Nor would he receive it, because whatever separation occurred because of jurisdictional issues, Fall River union leaders with the exception of Jackson were united through their common faith against socialism, the worst of modern heresies. These were influential laymen who on a daily basis lived out their lives guided by the message contained in the 1905 book Socialism and Christianity (a French translation, Socialisme et Christianisme, was printed in the neighboring city of New Bedford in 1906) authored by the erudite first bishop of Fall River, William Stang, D.D. Golden was first and foremost in bringing the perspective of his Church into the marketplace as a member of a Catholic labor organization, the Militia of Christ, condemned by the Wobblies “as an agent of ‘that great international whore – – the Roman Catholic Church.’”

Golden was guided by his conservative philosophy in the years after the Lawrence strike. He was proud to travel with Gompers to Europe in 1918 as a union labor commissioner with a mission to encourage British and Italian workers to share their patriotic fervor in supporting the war effort. Before, during, and after World War I Golden and his labor officer colleagues murmured not a word of protest when the Chief of Police interfered and prevented IWW speaking engagements throughout Fall River. He carried his 100 percent Americanism to the extreme, even encouraging hundreds of his unionists to go on strike against one mill corporation solely because management refused to fire eleven “Bolshevists.”

Contemporary “radicals” continued to condemn their nemesis as unresponsive to the needs of the most disadvantaged mill workers. Yet, by being who he was, Golden championed the textile downtrodden because of what he represented in a way that the IWW would have found impossible to emulate. Golden turned his attention away from an exclusive focus on the foreign born of the North by focusing on domestic workers of the South. His fearless union organizing travel through textile sites in that region were certainly unwelcome by mill management but were at least tolerated in a way that any IWW “invasion” would not. Furthermore, Golden gained results. By 1920 more than one quarter of UTW membership came from the South and had been organized on an industrial basis model. Golden was motivated to help these workers to help themselves and in the process was attempting to shrink the wage differential that was a drag on northern textile worker pay, and a distinct threat to mill closures in his home region. These UTW affiliated workers were militant enough to conduct a strike in the year of Golden’s death. Though defeated and virtually wiped out, the seeds of trade unionism were planted, and would regenerate during the Great Depression with southern unionists primary participants in the 1934 textile uprising, the largest strike in American history to that point in time.

The IWW would also view as abhorrent Golden’s bourgeois quest for respectability. But Golden did achieve parity with the political and clerical leadership of his home community, which provided additional social leverage at the state level. His was a voice to be heard and to be reckoned with. Well connected with the Democratic Party and its local political leaders, including by being a national Democratic Party committeeman, Golden took advantage of his hard-earned status by working on behalf of child laborers.

Ever since 1867 Massachusetts had been a leader in child labor protection laws, but recalcitrant management resisted by willful disobedience and political lobbying. Golden played a leadership role in organizing a successful campaign to defeat a notorious anti-labor governor’s bid for re-election to office in 1904 (“If the governor wishes small children to work in textile establishments at hours when most people are in their beds, he is not fit to occupy the executive chamber again.”) Thanks in no small part to his eternal vigilance, Massachusetts by 1908 had the least violation of child labor laws in the nation. At the time of the Lawrence strike, Golden was serving as a member of the Massachusetts Child Labor Commission. Golden’s reputation as a “bitter opponent of child labor” earned him the respect of reformers, and he was invited to lecture and share the podium before audiences of teachers and social workers with the likes of Lincoln Steffens and Progressive child advocate and playground reformer Joseph Lee.

When Golden died at age fifty-eight, his passing was marked by plentiful flower arrangements but an absence of flowery oratory. He was remembered as the labor leader who had been most vilified in the country. Because of his pugnacious nature, it was implied, he had brought unnecessary troubles upon himself. (“John Golden was once attending a meeting of the emergency committee of the organization when the secretary read up [from] a letter in which one of the local unions attacked Mr. Golden in a most insulting manner, charging him with a line of conduct to which no self-respecting man would stoop, and in conclusion, more in the way of a dare, than an invitation, intimating [t]hat Mr. Golden might visit the local on a certain night and hear more charges of the same character. Mr. Golden did not say a word about the contents of the letter, but took out of his pocket a note book in which he kept memoranda of his engagements. After seeing that he had no conflicting appointment he remarked philosophically, 'Tell them I'll be there.'") It was stated that his tactlessness had cost the UTW some unnecessary defections over the years. But it couldn’t be denied that Golden had also evolved, and no longer shared the elitist resistance of other local craft unionists against organizing “the foreign elements.”

In death, as in life, the social divisions of his adopted city were glaringly apparent. No self-respecting Catholic at that time would be buried in the public (read Protestant) cemetery, final resting place of the old Yankee families who by common perception within the Irish community had been all powerful oppressors. Symbolically, a cemetery benefactor who had been Fall River’s foremost industrialist built the most physically dominant gravestone in his own memory.

Golden’s burial would instead be at St. Patrick’s Cemetery whose very name gives indication that the Franco community would also remain separate in death by developing its own cemetery of Notre Dame at the opposite end of the city. In terms of size and location, Golden’s gravesite is as prominent as the aforementioned manufacturer’s gravesite is at the city’s primary cemetery. In this sense, the once disadvantaged Irish community had over time achieved a modicum of parity.

This is, in part, a tribute to the intrepid organizer Golden. Though the IWW had withered away, Golden had brought the UTW to its zenith of power. In one sense he was fortunate in not being around for the remainder of the 1920s to witness labor’s problems as the textile “sick industry” became depressed, with negative consequences for its workforce that by then had an even larger component from southern and eastern Europe.

That Golden reacted with at least partial discomfit toward “new” immigrants was undeniable. But the chief reason for his stance on immigration was that greedy capitalists were selflessly promoting an unrestricted situation.

Golden, the “old” immigrant, and all his contemporary Fall River union leaders, though often separated by jurisdictional disputes, shared the common bond of leaving England under duress. Their commitment to strengthening workers through united action was based on prideful collective memories of having defiantly resisted oppression. But their philosophical outlook was also shaped by the fact that they had lost and had paid dearly for their militancy. None more so than Golden, who, after enduring blacklist unemployment, left behind siblings and further eroded his economic security because of transportation costs associated with bringing his family to Fall River, including his wife and mother-in-law. The disruption experienced by four children between the tender ages of four and nine must not have improved Golden’s frame of mind.

It would have been understandable that his IWW critics would view Golden as a well-paid union executive, one of the AFL “labor aristocrats” who was maintaining a nice office in New York at the time of his death and could not relate to textile workers’ daily trials and tribulations. While he, in fact, did have minimal economic security in the latter stages of his career, Golden remained immersed in a working-class culture. Golden always paid rent and resided in a tenement house on a street whose homes were filled with cotton mill workers. His immediate family depended on mill employment; it was not until one of his twenty grandchildren became a schoolteacher that white-collar status was achieved within his family. He could also remember hard times on this side of the Atlantic. Bad timing meant that the Goldens had experienced the eighteen-week strike of 1894. Three of his children were textile employees when factories closed during the “Great Strike”. His daughters and granddaughters were working primarily as weavers at the time of Golden’s death and had been doing so since their early teens. His son Henry trained as a young backboy in a mule room as he sought to emulate his father’s vocation. Thus, Golden’s passion as a champion of child labor reform was aimed at correcting an evil that many of his co-reformers had not experienced personally.

Also, though his IWW critics viewed him as a weak pawn of management, and though there were times in his career where he was willing to give management the benefit of the doubt, and though he worked for compromise solutions that would prevent strikes (“I’ll go 10 miles out of my way to avert a strike”), Golden would fight bad employers like Wood with ferocious determination. He also championed fairness for workers at the hands of the political system and the judiciary. For all the enmity he harbored toward Ettor, Golden castigated the authorities responsible for the Wobbly hero’s arrest on trumped up charges.

He was convinced that the UTW acted to “hasten the emancipation of our people from long hours, low wages, and inhuman conditions.” Under his direction, the UTW was instrumental in achieving a forty-eight-hour law in 1918 (as it had been in influencing passage of the fifty-four-hour law of 1912 that had brought on the Lawrence troubles), and rather than being satisfied immediately began pushing for a reduction to forty-four hours. Golden left his organization in a position of strength whereby the UTW was able to lobby successfully, even in the conservative 1920s, against a concerted effort by industrialists and their political allies to roll back hour legislation victories, preserving Massachusetts’ reputation for reform.

Golden’s end goal of promoting worker welfare went beyond the mill place to encompass all of society. His entire acquired value system just didn’t match up with the leftist approach to social justice. He was an honest and devoted Catholic trade unionist committed to following and implementing his contemporary American priest John A. Ryan’s living wage moral mandate, as well as following the dictates of Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum.

The IWW would have found the clasped handshake symbol of the UTW carved into his tombstone laughable, remembering its president as a divider rather than a unifier. The accompanying written inscription would have elicited further derision should any Wobbly have wandered by (unlikely!). But to the burgeoning membership of 105,000 (contemporary newspaper accounts would have impressed readers by providing estimates of 175,000-200,000), the monument was well worth it. John Golden, by all accounts, was a person with an enormous capacity for work who reflected their view of life and served them well. UTW delegates had selected him as their president at nineteen consecutive annual conventions and expressed this sentiment regarding their fallen leader for the edification of gravesite visitors: “WHAT GREATER SACRIFICE COULD A MAN MAKE THAN TO LAY DOWN HIS LIFE FOR THE SAKE OF LABOR AND HUMANITY.”