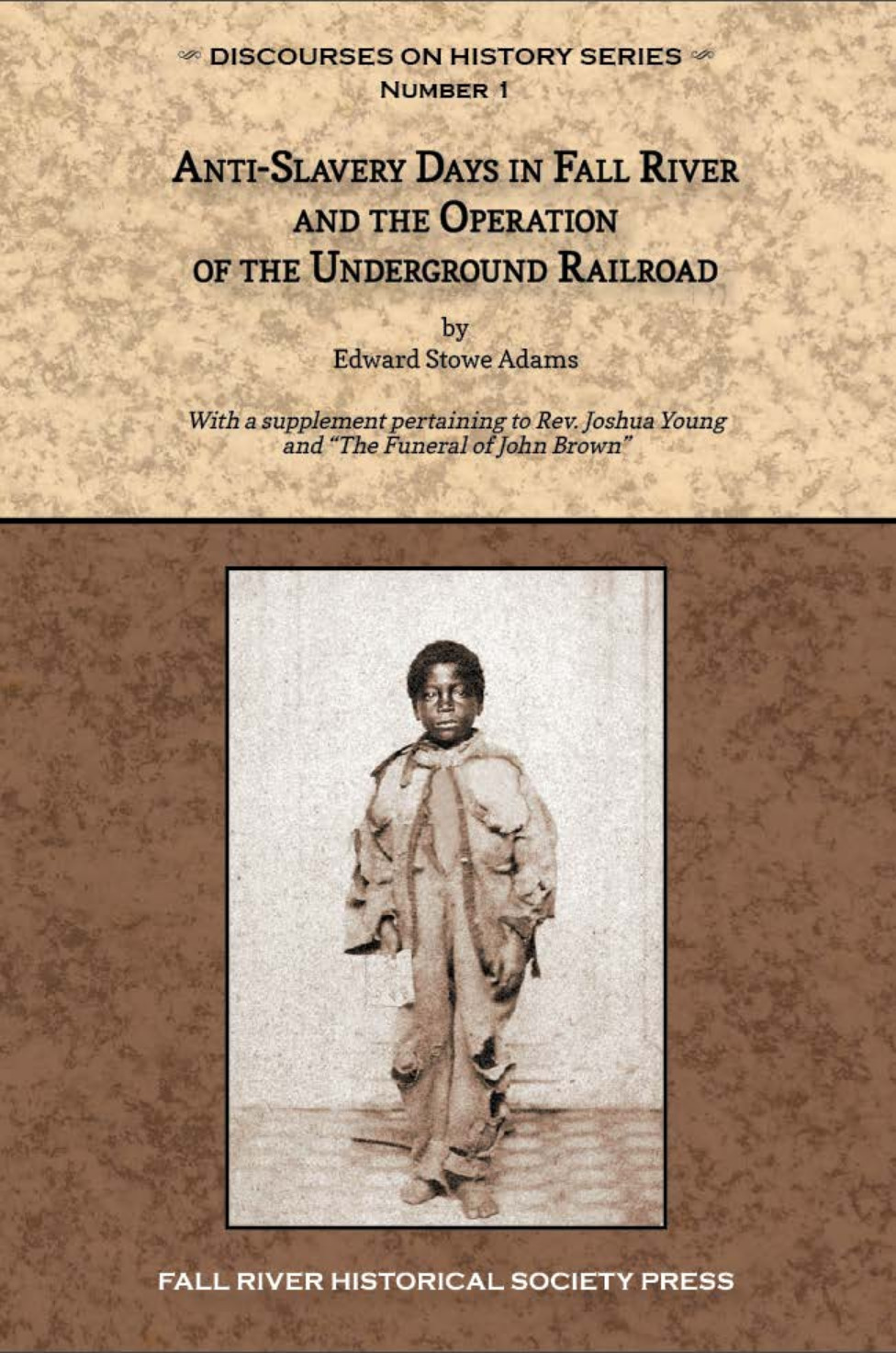

ANTI-SLAVERY DAYS IN FALL RIVER AND THE OPERATION OF THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD by Edward Stowe Adams, supplemented by the Fall River Historical Society

Editor's Note:

On the evening of Monday, May, 23, 1938, Edward Stowe Adams presented his paper, “Anti-Slavery Days in Fall River and the Operation of the Underground Railroad,” illustrated with fifteen glass lantern slides, to the members of the Fall River Historical Society in the parish hall of the First Congregational Church; the presentation was extremely well received, later being presented in serial form in the Fall River Herald News.

Contained in this volume is an expanded version of Adam’s original manuscript, which is housed in the Charlton Library of Fall River History at the Fall River Historical Society. The format of this manuscript has been slightly edited for punctuation and readability, with italicized information in square brackets added for the purposes of clarification and context. Illustrations include the fifteen original images selected by the author, supplemented with additional images pertinent to the text.

About the Author: Edward Stowe Adams

Edward Stowe Adams (1856-1948) was a lifelong resident of Fall River, Massachusetts. An original incorporator of the Fall River Historical Society, he was an extremely active member of the organization, serving as director and president, and was noted as the “dean of Fall River historians.” Blessed at birth with an inquisitive mind, handsome features, and cultured, progressive parents, he was reared in an enlightened household; the strong moral convictions, and civic and social responsibilities, instilled by his parents were mainstays throughout his long life.

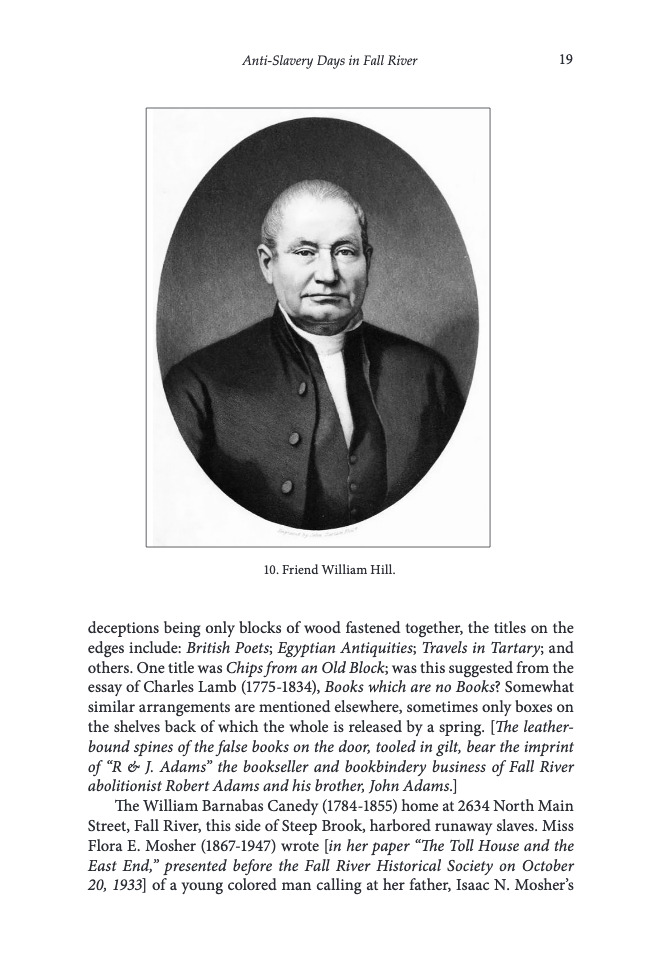

His father, Robert Adams (1816-1900), was born in Ayr, Scotland, and immigrated to the United States with his parents as a child. He settled in Fall River in 1842 and established Adams Bookstore, a bookbindery, bookselling, and stationery business that was recognized as the most successful concern of its type in the city. Reams of paper and countless ledgers in myriad styles were needed to record the day-to-day business transitions of Fall River’s lucrative textile mills, and numerous extant volumes of that nature bear the imprint of Adams Bookstore, a concern eagerly disposed to supply the demand. Throughout his lifetime, he was closely identified with the civic, political, and humanitarian affairs of his adopted city. A staunch abolitionist and active participant in the Underground Railroad in the decades prior to the Civil War, he habitually “conducted” fugitive slaves en route to freedom in Canada to safe houses in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. At the time of Robert Adams death, his obituary noted that “he made for himself an enviable record as a philanthropist. Not only did he give his money and moral influence toward the elevation of mankind, but a degree of hard personal effort was also contributed.”

Edward’s mother, née Lydia Ann Stowe (1823-1904), a native of Dedham, Massachusetts, was born into a progressive, well-educated family with ties to Fall River. She was a member of the first class of the Massachusetts State Normal School in Lexington and, as such, was one of the first professionally trained teachers in the United States; maintaining a lifelong interest in education, she was the first female member of the Fall River School Committee.

A devoted abolitionist, and early advocate for women’s rights, she was an active participant in many charitable and educational affairs in Fall River, where she relocated after her marriage in 1844. She was a founding member of the Fall River Women’s Union, an organization that assisted working women in various capacities, “regardless of race, religion, or class.” Recognizing the necessity for the care of the elderly, particularly women, she and her husband donated a choice parcel of land on Highland Avenue upon which was constructed the Home for the Aged; opened in 1898, the organization, until 2018, served the needs of the elderly, operating as the Adams House in recognition of that family’s longstanding support.

The Adams family welcomed many notable guests in their residence, providing young Edward the opportunity to become acquainted with many of the luminaries of the day, among them Frederick Douglass (c.1818-1895), who he remembered as “a personal friend of my father and … a man of commanding presence,” and Sojourner Truth (c.1797-1883), who, he recalled, was “entertained for several days at our home.” Of the latter, he said she “sold her pictures at lectures saying, ‘I sell the shadow to support the substance.’”

The erudite young man was educated privately during his formative years, graduated from the Fall River High School with the class of 1872, and was prepared for college at the West Newton English and Classical School in West Newton, Massachusetts. Entering Brown University, he was awarded a Bachelor of Philosophy in 1879.

His education complete, he returned to Fall River and entered his father’s lucrative firm, from which he retired in 1917; additional business interests included investments in textile mills and banking concerns, on whose boards he served in various high-level capacities. Following the path laid by his parents, he became increasingly engaged in civic affairs and altruism, being considered a “leader in the city’s educational and cultural progress,” and “a cheerful, enthusiastic, and forceful worker for the public good.” Raised in the Unitarian faith, he was an active member of his congregation, and served as church moderator for a number of years.

Well-traveled in the manner of the Grand Tour, he made numerous lengthy trips abroad, visiting the historical and cultural capitols of the world, in addition to more exotic, lesser-known locations. He married his first wife, née Eva J. Palmer (1856-1895), a native of Dover, New Hampshire, in Fall River on October 12, 1886; she died in 1895. Two years later, on July 29, 1897, he married, in Dedham, Massachusetts, Carrie Maria Smith (1855-1935), a native of that town. The second Mrs. Adams died in Fall River in 1935. Both unions were childless.

According to his friend and fellow historian, Arthur Sherman Phillips (1865-1941), Adams wrote “several important papers [and] articles … all of which showed diligent research.” Phillips further credited Adams with “render[ing] aid of great value [and] furnishing valuable information which has made several articles more accurate and complete” in his groundbreaking three-volume Phillips History of Fall River, published posthumously in 1944, 1945, and 1946.

Following Adams’ death at the age of ninety-one on February 18, 1948, his obituary accurately noted that “his historical papers have served to perpetuate much important data pertaining to the city’s background and progress which would otherwise have been lost to posterity.”

It was a fitting epitaph to an extraordinary gentleman.

To purchase a copy of this book for $14.95, plus $6.50 Shipping/Handling, please call us at 508-679-1071, ext. 105.

Read a free excerpt from ANTI-SLAVERY DAYS IN FALL RIVER AND THE OPERATION OF THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD by Edward Stowe Adams (pages 1-21)

BLACK SERVICE WORKERS ON THE OLD FALL RIVER LINE

“On the Old Fall River Line," recorded 1913 by William Thomas “Billy" Murray (1877-1954).

From 1847 to 1937, the steamships of the famed Fall River Line, so-called “floating palaces” – in fact, floating luxury hotels – were important employers for large numbers of black service workers, who filled the positions of waiters, cooks, bartenders, and porters, among others.

The hours were long and required spending time away from ones family, but the pay was considered good for the time, especially for individuals employed in managerial capacities in the Stewards Department, which oversaw the food, beverage, and housekeeping needs of the passengers and crew.

According to Myra Beth Young Armstrong, in her book Lord, Please Don't Take Me in August: African Americans in Newport and Saratoga Springs, 1870-1930:

The steamboats of the Fall River Line were in fact the major employers of Newport's black service workers throughout the period. These steamers were more than mere functional vehicles. They provided luxurious, hotel-like accommodations for their passengers. … As 'floating hotels,' the steamboats required the same kind of workers, with the exception of their nautical crews, as did conventional hotels. African Americans filled these slots. In Priscilla of Fall River, a historical novel depicting life aboard the steamboat Priscilla, first launched in 1894, the author described a boarding scene: 'Scores of blue-uniformed, white-gloved, negro porters were lined up in orderly array to assist the several hundred travelers with their baggage.' The pages of the Fall River Line Journal regularly showed photographs of black crew members. Erick Taylor, a white native Newport, concurred with this impression of black-run steamers. He recalled: 'A great industry for black people … in Newport was the New York boats. They were the pursers and the workers on the boats. They'd be all the carriers and porters and things like that. And they'd be the waiters in the dining room. The waiters were very well paid. In addition to be being waiters and being paid for that, they also were helping them load and do other things. The New York boats were frankly directed by black people … The captains were always white people, but they [the blacks] would actually run the boat. They'd have three hundred or four hundred people on the boat and they had to feed and wash them, as it were.'

This exhibit contains images and material celebrating the strength and character of these hard-working individuals, without whom the so-called “Glory That Was” of the famed Fall River Line would not have been possible.

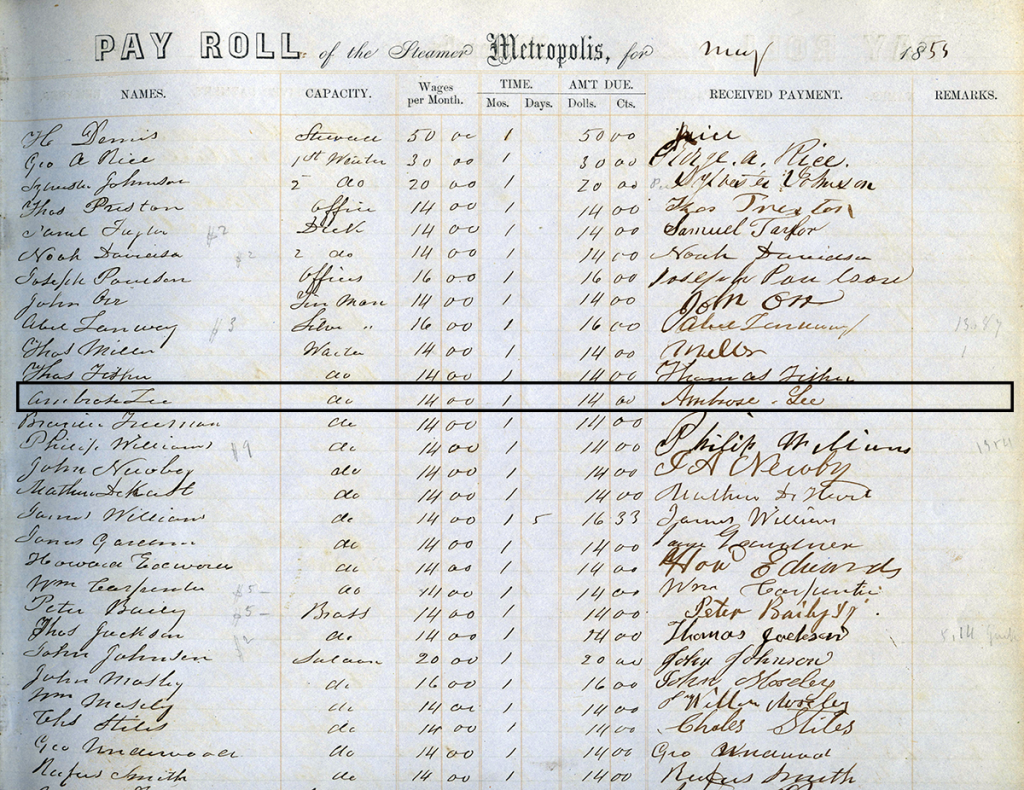

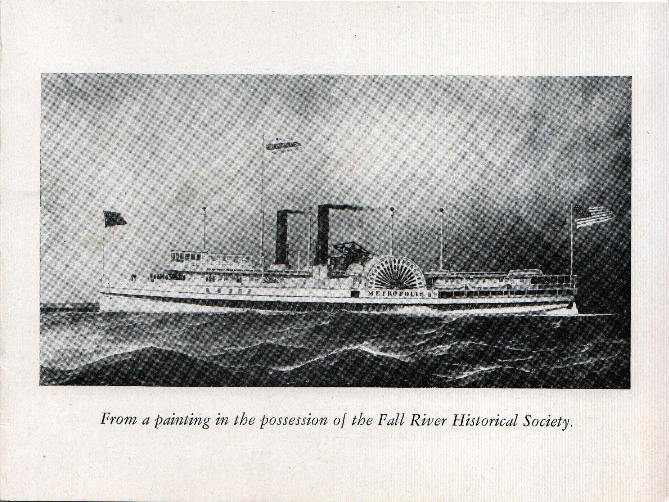

Steamer Metropolis :

Detail from the Pay Roll Record, Steamer Metropolis, May, 1855. Ambrose Lee (born 1829), a resident of New York City, identified in the 1850 United States Federal Census as “Black,” was employed on the vessel as a waiter at the monthly salary of $14.00.

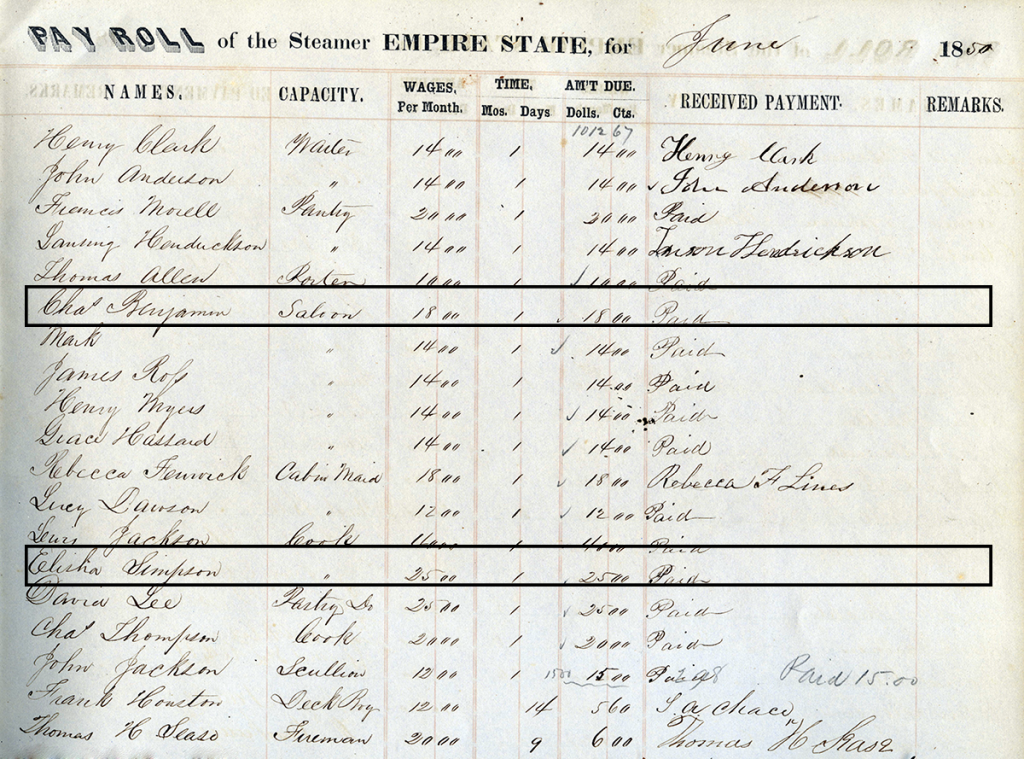

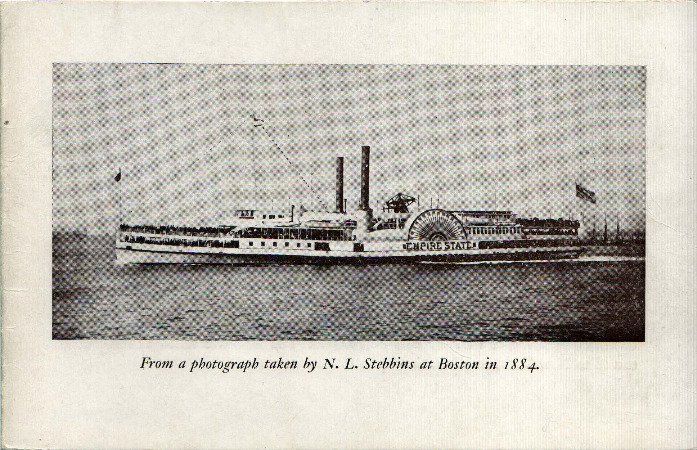

Steamer Empire State :

Detail from the Pay Roll Record, Steamer Empire State, June, 1850. Fall River, Massachusetts, resident Elisha Simpson (c.1826-1857), identified in the 1850 United States Federal Census as “Black,” was employed on the vessel as a cook, earning a monthly salary of $25.00.

Another Fall Riverite, Charles Benjamin (born c.1825), also identified in the 1850 United States Federal Census as “Black,” was employed as a “Saloon” attendant, earning a monthly salary of $18.00. The term Saloon refers not to a drinking establishment, but instead to a large public room inboard of staterooms on a steamship.

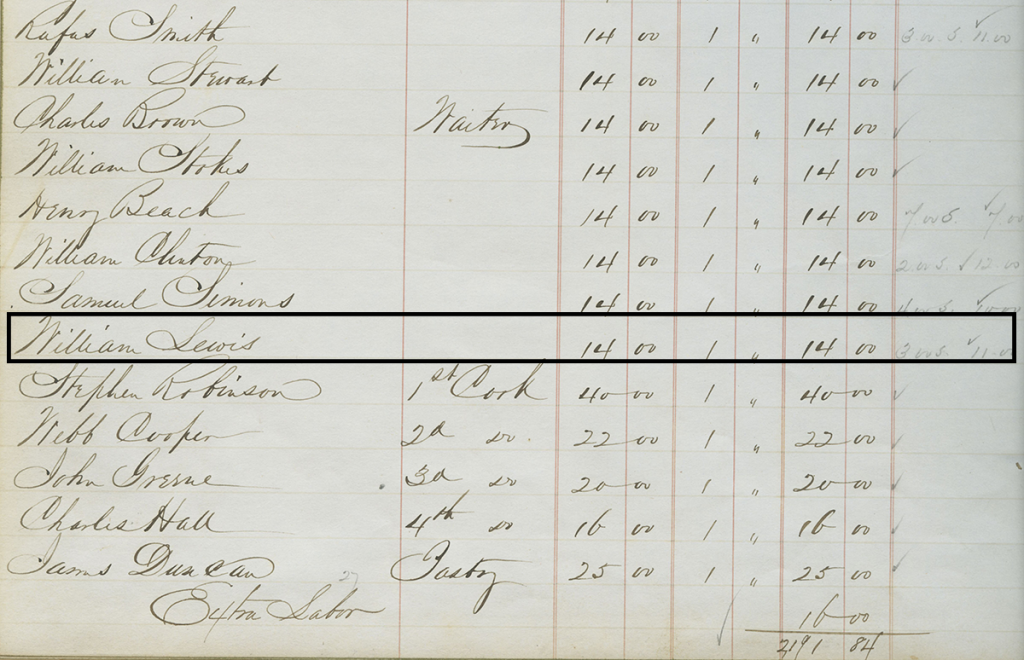

Detail from the Pay Roll Record, Steamer Empire State, December 1862. William Lewis (1819-1873), a Fall River resident identified in the 1850 United States Federal Census as “Mulatto,” was employed on the vessel as a waiter, earning a monthly salary of $14.00. Seven years after Ambrose Lee was employed in the same capacity on the Steamer Metropolis, the monthly salary for a waiter on the Fall River Line remained the same.

As an example of upward mobility, William’s daughter, Sarah Anna Lewis (1846-1939), later the wife of Edward A. Williams, was an 1869 graduate of Bridgewater Normal School, and the first African-American school teacher in Fall River. Another daughter, Mary Wilson Lewis (1847-1924), was the wife of the brilliant inventor, engineer, and author, Lewis Howard Latimer (1848-1928), who achieved recognition for his work in patenting the incandescent light bulb — working with Thomas Alva Edison — and the telephone — working with Alexander Graham Bell.

In 2017, the Fall River Historical Society explored the life of Sarah Anna Lewis and her family. You can read that research here.

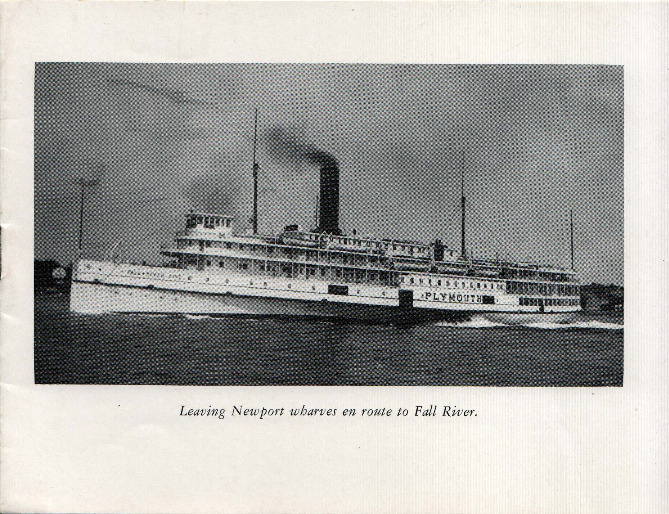

Steamer Plymouth :

The Quarter Deck, from which passengers would board and alight, Steamer Plymouth, late 1920s; a staged photograph depicting travelers and employees. (Irving Underhill Commercial Photography, New York, New York.)

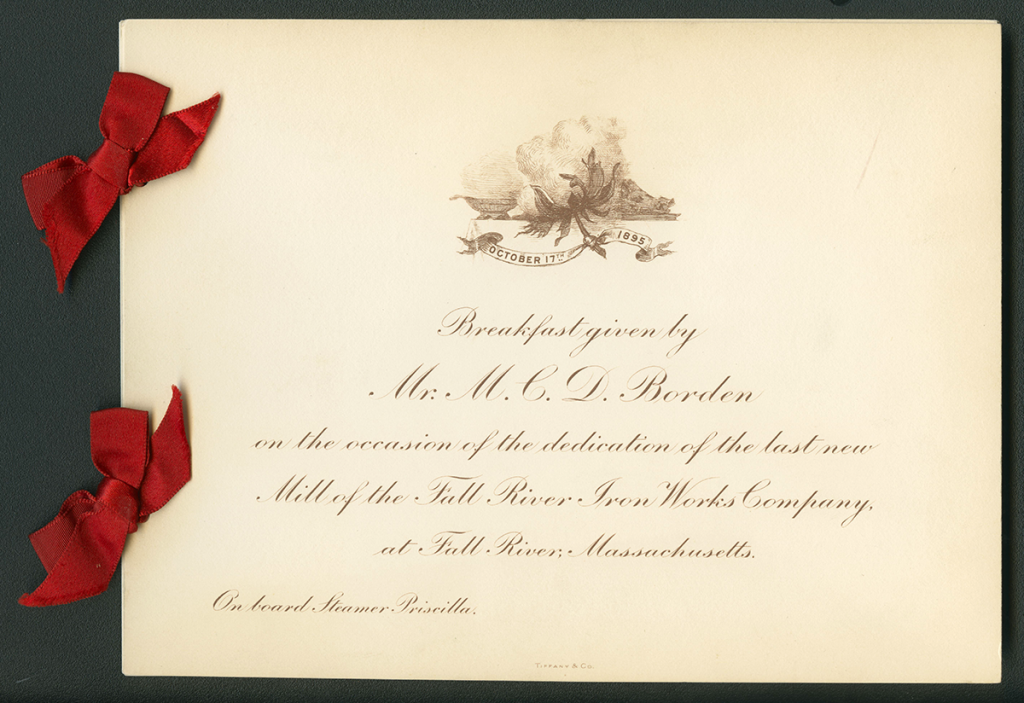

Steamer Priscilla :

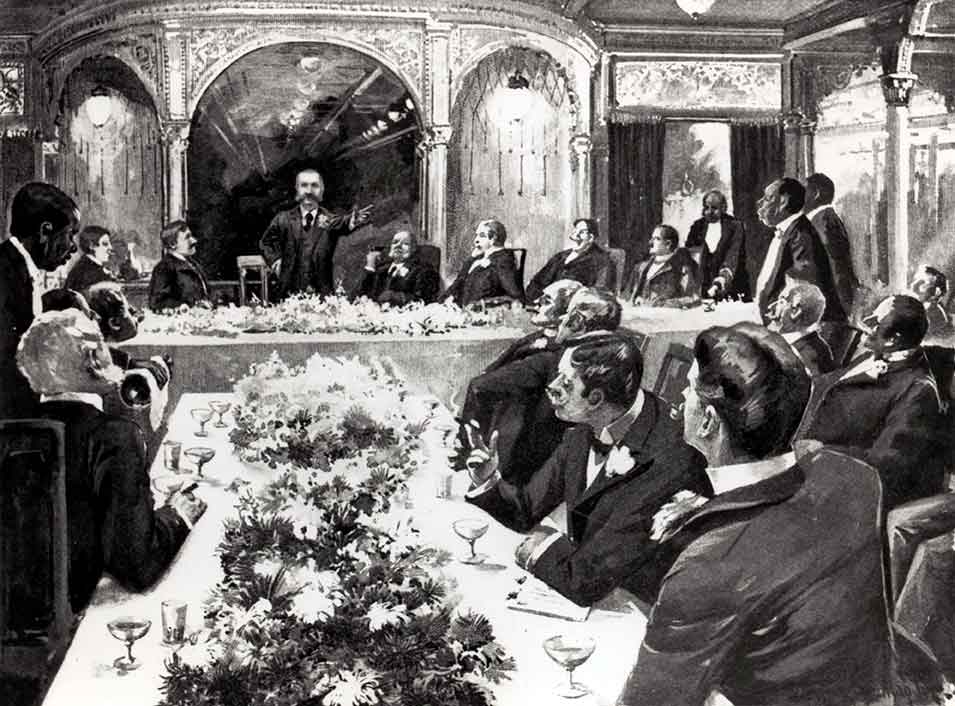

An illustration titled “The Breakfast," painted in 1895 by the American artist William Louis Sontag Jr. (1869-1898), depicting an elegant private breakfast held on board the Steamer Priscilla by the industrialist Matthew Chaloner Durfee Borden (1842-1912) on October 17, 1895. Members of the ship’s efficient wait staff can be seen in the painting. (John Gilmer Speed, A Fall River Incident or A Little Visit to a Big Mill. New York, New York: Press of J.J. Little & Company.)

An illustration titled “The Breakfast," painted in 1895 by the American artist William Louis Sontag Jr. (1869-1898), depicting an elegant private breakfast held on board the Steamer Priscilla by the industrialist Matthew Chaloner Durfee Borden (1842-1912) on October 17, 1895. Members of the ship’s efficient wait staff can be seen in the painting. (John Gilmer Speed, A Fall River Incident or A Little Visit to a Big Mill. New York, New York: Press of J.J. Little & Company.)

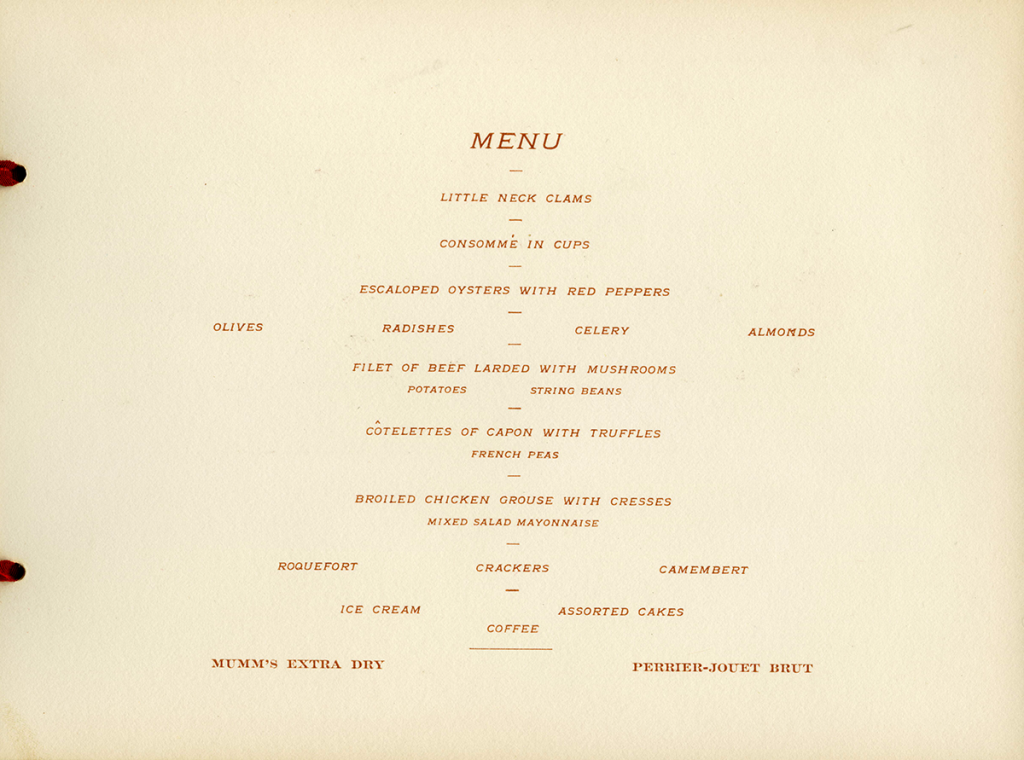

The breakfast menu, October 17, 1895; the deluxe souvenir menu was printed by Tiffany & Company, New York, New York. The sumptuous meal, washed down with copious quantities of Mumm’s Extra Dry or Perrier-Jouët Brut champagne was a credit to the Priscilla’s kitchen and wait staff: “Cooked most skillfully and served in a manner entirely credible to those who had it in charge … each person ate and drank what pleased him best, as though he were ordering … at Delmonico’s or the Waldorf.”

The Quarter Deck, from which passengers would board and alight, Steamer Priscilla, late 1920s; a staged photograph depicting travelers and employees. (Irving Underhill Commercial Photography, New York, New York.)

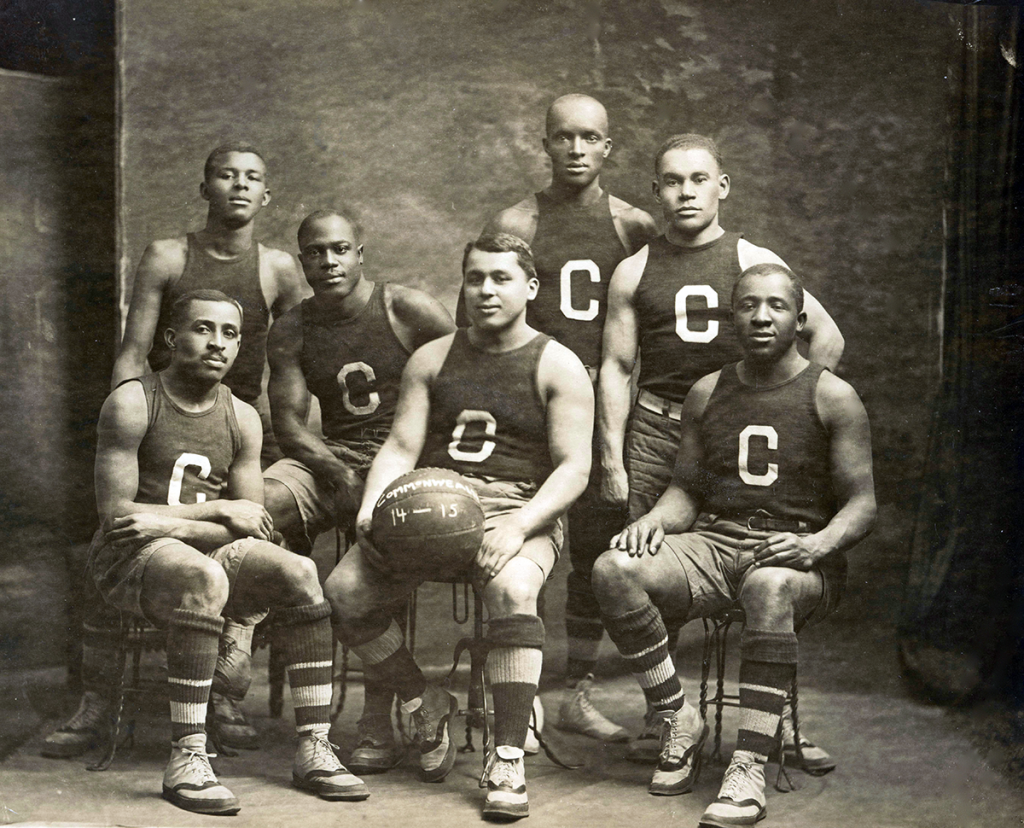

Steamer Commonwealth :

A rare image of the Steamer Commonwealth basketball team, 1914-1915; in addition to basketball, the Commonwealth crew also formed a baseball team. (Temple D. Parsons, Fall River, Massachusetts.)

The elegant dining room “on the roof” of the Steamer Commonwealth was decorated in the Louis XVI style and had a seating capacity of three hundred. This circa 1914 photograph was captioned: “The acme of luxury of modern travel.” (Unidentified photographer.)

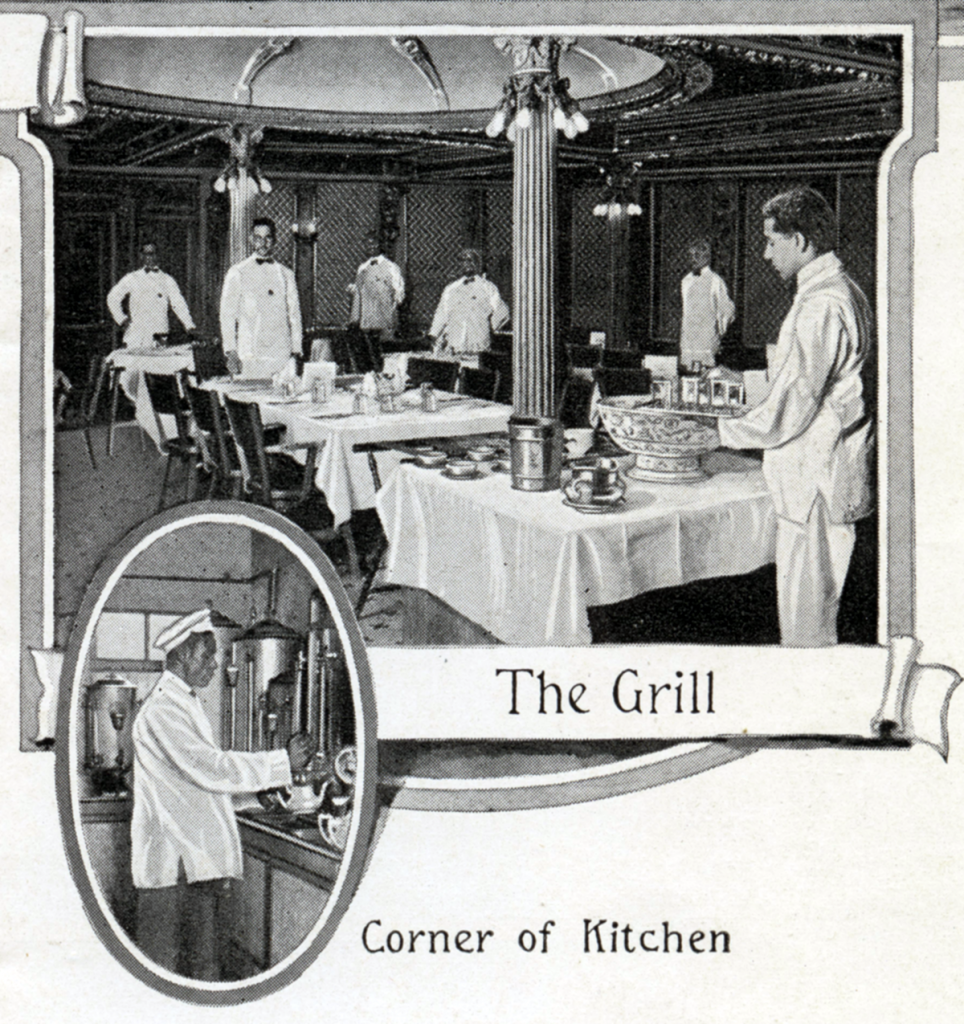

A bartender prepares a cocktail in the Roof Garden Grill Room of the Steamer Commonwealth, late 1920s; decorated in the English Renaissance Style, it was less formal than the dining room. (Oliver Lippincott, New York, New York.)

Another view of the Roof Garden Grill Room on the Steamer Commonwealth, late 1920s; “one [could] enjoy the comforts of his favorite chop-house.” (Oliver Lippincott, New York, New York.)

An illustration from a Fall River Line publication depicting “The Grill” and a “Corner of [the] Kitchen,” Steamer Commonwealth, circa 1927.

A so-called Coffeeman filling silver-plated coffee pots in the kitchen of the Steamer Commonwealth, late 1920s. (Ewing Galloway, Photographic Illustrations, New York, New York.)

Kitchen staff of the Streamer Commonwealth, with their batterie de cuisine. This circa 1914 photograph was captioned: “The kitchens are spic-and-span and up-to-date.”

For each overnight voyage the ship’s kitchen staff would receive – and prepare – a staggering amount of supplies including: “a ton of roasts, steaks, and chops; 200 lbs. of poultry; 240 dozen eggs; 500 loaves of bread; 100 gallons of milk; 300 lbs. of butter; 300 lbs. of fresh fish; 150 lbs. of salt fish; and 100 lbs. of coffee.” (Oliver Lippincott, New York, New York.)

A “Mr. Leslie from the Virgin Islands” preparing a roast chicken in the kitchen of the Steamer Commonwealth, late 1920s. (Ewing Galloway, Photographic Illustrations, New York, New York.)

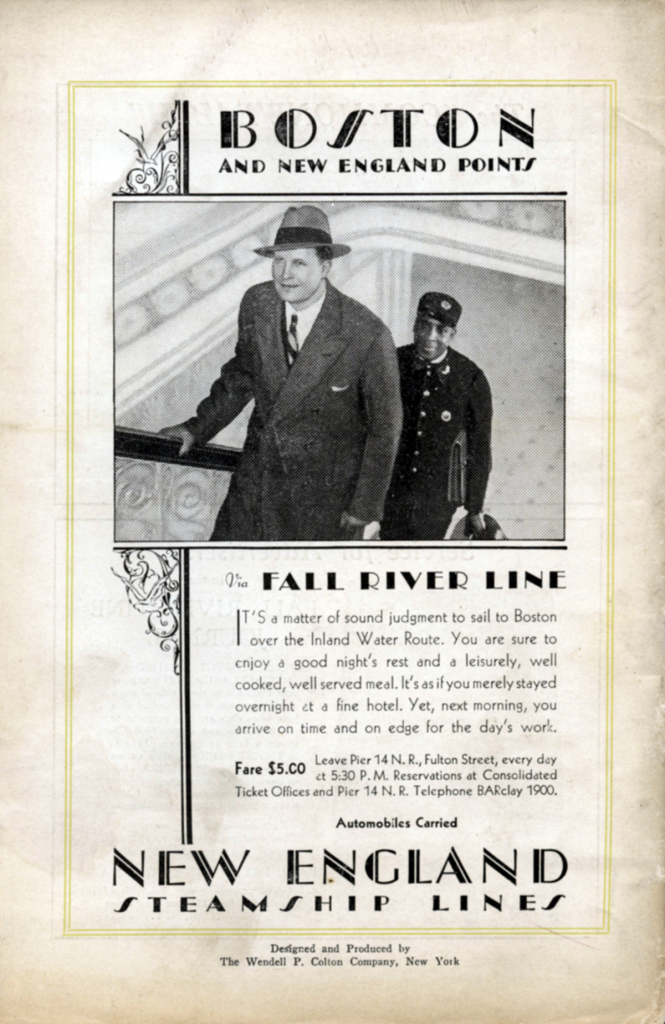

A back cover advertisement from the Fall River Line Journal, Vol. LII, No. 3, March 1930. The image speaks volumes and illustrates the racial inequality of the era: In the foreground, an impeccably groomed, well-heeled — and very white — businessman passenger, trailed by a subservient, ever-smiling — and very dark-skinned — porter. Extremely accommodating, he totes baggage — and attaché case.

A back cover advertisement from the Fall River Line Journal, Vol. LII, No. 3, March 1930. The image speaks volumes and illustrates the racial inequality of the era: In the foreground, an impeccably groomed, well-heeled — and very white — businessman passenger, trailed by a subservient, ever-smiling — and very dark-skinned — porter. Extremely accommodating, he totes baggage — and attaché case.

“Crew compelled to leave Commonwealth [during their strike] at Fall River, July 1937.” (Walter Whitman Coolidge Sr., Fall River, Massachusetts.)

According to Roger Williams McAdam in his Commonwealth: Giantess of the Sound, in 1937:

A threat against continuance of the steamers came from an entirely unexpected source. The American Federation of Labor and the new CIO, led by forceful Joseph Curran, began a bitter contest for control of New York's waterfront. Passenger service on the Eastern's Boston Line was suspended for several trips, due to conflicting demands of the rival unions. Then labor unrest on the Fall River Line flared into the open. On the evening of June 30 the Commonwealth had taken aboard at New York her largest passenger list of the season. The porters sang 'Happy days are here again'—the steamer had over nine hundred aboard, many of whom were children en route to summer camps. Captain Frank Avery was about to give the command 'Cast off,' when word came that a sit-down strike by essential members of the crew had begun. The westbound Priscilla was delayed at Fall River by the same unheard-of-tacts. At Pier 14, argument and persuasion failed; the crew would not sail. They wanted more money and better quarters. Agitated New Haven officials arranged for special trains to transport the Commonwealth's perplexed passengers to New England.

On July 12 crews on the railroad's New Bedford, Martha's Vineyard, and Nantucket Line 'sat down.' When, in sympathy with their island steamer brethren, the crews of the Commonwealth at Fall River and the Priscilla at New York 'sat down' they crushed the life out of the ninety-year-old Fall River Line.

The inactive crews refused to leave the steamers at either terminal. … The tedium lasted for several days. Then come the 'complete and awful surprise.' The railroad trustees decreed suspension of the service and the paying off of the crews. The Commonwealth never moved again under her own power!

This exhibit is an ongoing project,

so please continue to check back for further research and material.