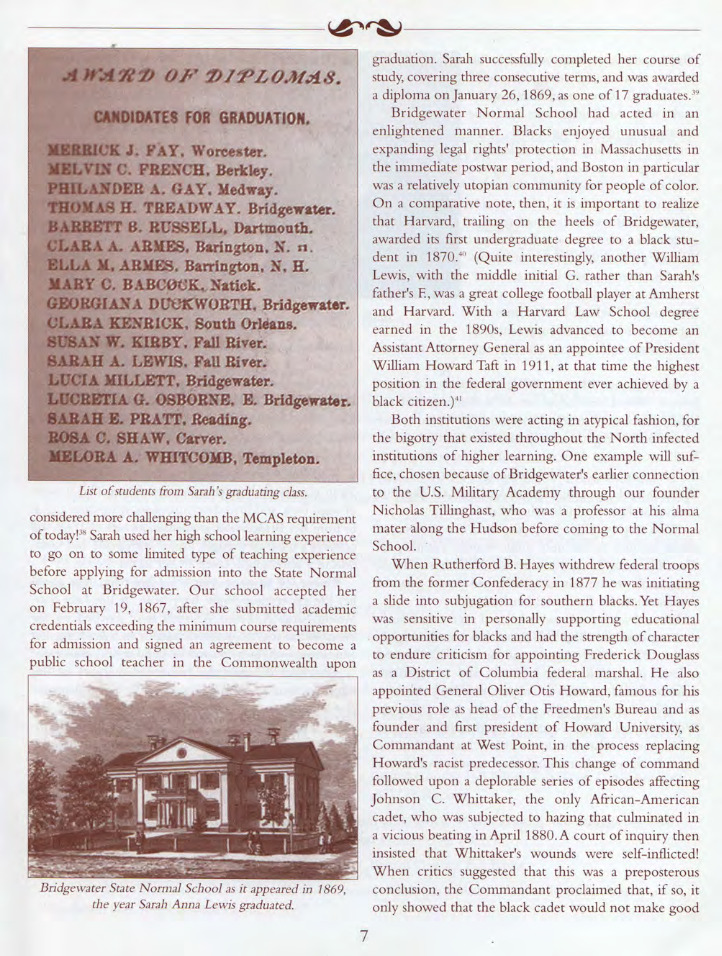

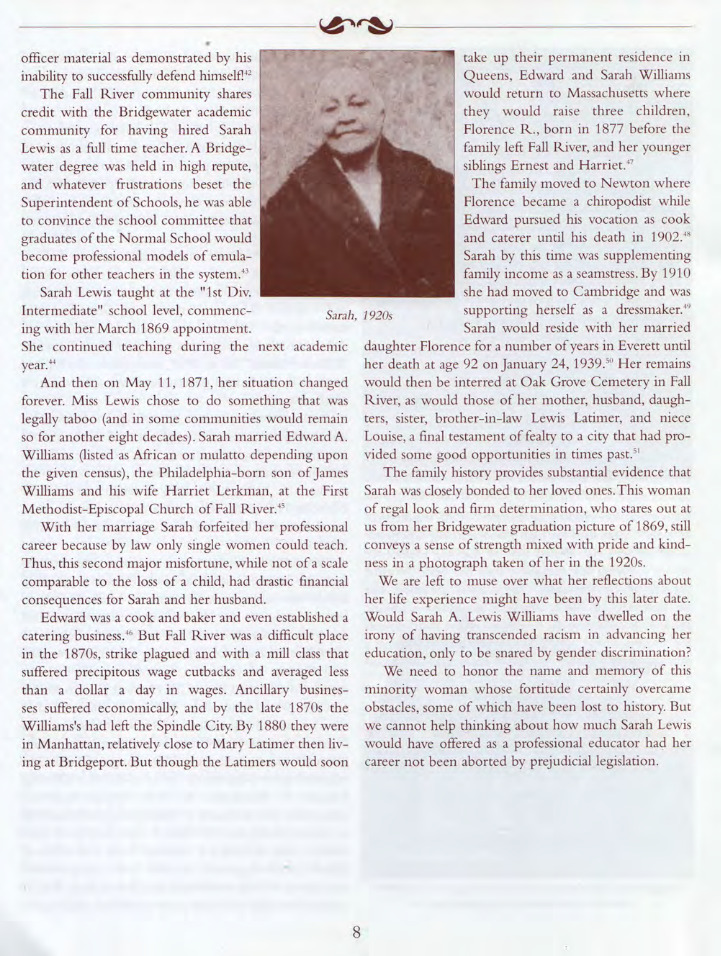

SARAH ANNA LEWIS by Philip T. Silvia, Jr., PhD

THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN FALL RIVER by Kenneth Champlin, supplemented by the Fall River Historical Society

What was the Underground Railroad?

Prior to the Civil War, the Underground Railroad was a system for helping fugitive slaves escape their masters. With the food, shelter, and advice given to these fugitives by Northern abolitionists, thousands of former slaves were able to escape to Canada, beyond the reach of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

Like many clandestine activities, the URR had its own secret language:

- Stations: Houses along the routes where fugitives could be secretly and safely sheltered.

- Conductors: Those individuals who aided those fleeing.

- Stockholders: Those individuals who contributed money, clothing, and other necessities.

Underground Railroad Routes

Small packets, or commercial sailing ships would leave the Virginia ports of Richmond or Portsmouth, with fugitives concealed onboard. These ships would reach New Bedford or Cape Cod, MA, where the stowaways would disembark. In New Bedford, mill owner Andrew Robeson dispatched the new arrivals to Nathaniel Briggs Borden in Fall River. From there, Robert Adams “conducted" the fugitives to Pawtucket, RI, or to the Valley Falls, RI, home of Samuel Buffington Chace and his wife, née Elizabeth Buffum. Leaving the Chaces, the travelers were placed on the Worcester-Vermont Railroad. Their final destination was freedom in Canada.

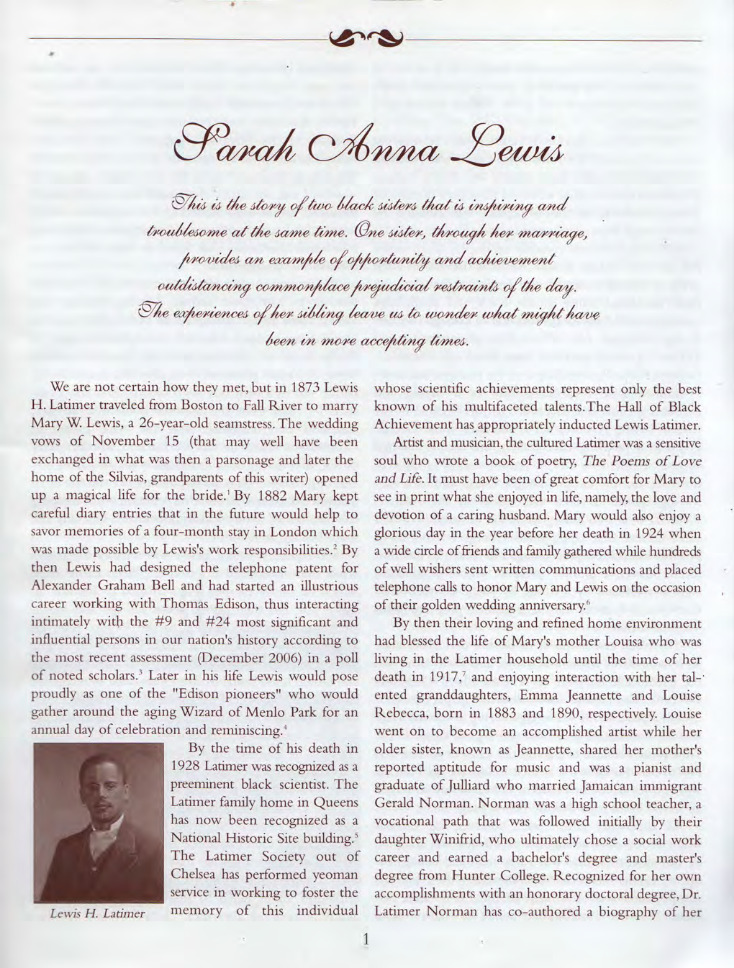

Fall River Map of 1850

This is the center of Fall River as it appeared in 1850. The residences of many of Fall River’s abolitionist families were in the area to the right of Main Street, particularly Rock and Pine Streets.

1871 Map of Fall River

This is how the city center appeared in 1871. Note the Quequechan River on the left as it passes beneath several of the city’s mills, such as the Troy Cotton & Woolen Manufactury, Pocasset Manufacturing Company, Quequechan Mills, and others. Already, the river that gave the city its name is partially concealed under buildings and streets.

Fall River Stations or Safe Houses

Originally, there were at least six known Fall River Stations on the Underground Railroad. One was the residence of Nathaniel Briggs Borden, 40 Second Street, the abolitionist third mayor of Fall River. Demolished in the 1930s, this station stood on the site occupied at the time of this writing by the Webster Bank. The other stations on the URR were: the Abraham Bowen house, 175 Rock Street; the Dr. Isaac Fiske house, 263 Pine Street; a double house where Albion King Slade and his wife, née Mary Bridge Canedy, lived, 335-337 Pine Street (190 Rock Street); the Fall River Historical Society, 451 Rock Street, when the house stood in the area of Columbia Street until it was moved in 1869; and the home of Squire William Barnabas Canedy at 2634 North Main Street. The Canedy house was on a more northerly branch of the URR that led to Cumberland, RI.

The Buffum Family

Arnold Buffum (1782-1859) was a Rhode Island abolitionist. He began his career as an entrepreneur, manufacturing and selling hats in Providence, RI, and also patented some inventions concerning this trade. He married Rebecca Gould (1781-1872) and they had seven children. Buffum was a Quaker, which greatly influenced his views on slavery. He joined with William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1875) and others to establish the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832. He was the new organization’s president and the first roving lecturer. By the late 1830s, he broke with Garrison, and with James Gillespie Birney (1792-1857) founded the Liberty Party in 1840. Buffum was also an advocate of temperance, and his daughter Elizabeth (1806-1899), the wife of William Buffington Chace (1800-1870), also went on to become a prominent abolitionist and a leader in the movements of women’s rights and prison reform.

Robert Adams

Robert Adams (1816-1900) was born in Ayr, Scotland. His family moved to New Brunswick, Canada, then to Pawtucket, RI, in 1823. After he arrived in Pawtucket, Adams worked for Samuel Slater (1768-1835), and later became a grocer and eventually learned book binding there. He arrived in Fall River, MA, in 1842 and opened a book binding store. He added the sale of books to his business and, by the 1870s, relocated to the Borden Block (Academy Building). He and his wife, née Lydia Ann Stowe (1823-1904), an educator, became increasingly active in the abolitionist community. Prior to the Civil War, Adams became a conductor on the Underground Railroad often conveying disguised fugitives in a closed carriage from the home of Nathaniel Briggs Borden to the Valley Falls, RI, home of Elizabeth (Buffum) Chace, Mr. Borden’s Quaker abolitionist sister-in-law.

The couple “sacrificed social prestige, money, time and labor in the promotion of the anti-slavery movement, and they afforded shelter to those who were pursued because they were slaves, and to whom the ‘underground railroad’ gave the only means of safe and rapid transit to Canada. The speaker for freedom was always welcome at their board, whether black or white, orthodox or heterodox."

Among Adams’s friends were: Harriet Tubman (1820-1913), the heroic URR “conductor” who famously “never lost a passenger”; Sojurner Truth (1820-1913), who “lectured in Fall River after the Civil War and spent nearly a week” as a guest at the Adams residence; and Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), who was a frequent lecturer in Fall River. According to Edward S. Adams, the latter “became an intimate friend of my father … spent the night at our home," and, in about 1890, “made a special visit” to Fall River “to see my father.”

Fall River Stations on the Underground Railroad

Abraham Bowen House, 175 Rock Street

According to Edward Stowe Adams (1856-1948), the son of Robert Adams, the Abraham Bowen (1803-1889) residence on Rock Street was a station on Fall River URR, where Bowen “a strong abolitionist … cared for runaway slaves." A mill stockholder, Bowen was described as a local eccentric who published and edited a weekly topical newspaper called the Fall River All Sorts. He was alternately a grocer, printer, livery stable keeper, and purveyor of botanic medicines.

Squire Canedy House, 2634 North Main Street

The house at 2634 North Main Street, Fall River, MA, was built in 1806 by William Barnabas Canedy (1784-1855) upon his marriage to Susan Hughes Luther (1787-1858). The Squire served as a postmaster at the Steep Brook section of Fall River, as well as in the General Court (as the legislature was once called). He was also appointed to a committee to lay out the North Burial Ground in 1825. The Squire and his wife had thirteen children, seven of them daughters, and all seven girls taught in the Fall River public schools. Two of his daughters, Betsey Leonard Canedy (1816-1898) and her sister, Anne Chaloner Graves Canedy (1821-1866), travelled south toward the end of the Civil War to teach the children of freed slaves (called “contrabands," prior to Emancipation). Both sisters wrote letters home describing conditions in these new schools, which were sometimes close to Civil War battle lines. Excerpts from their letters can be found in Edward S. Adams’ articles.

335-337 Pine Street (190 Rock Street)

Albion King Slade (1823-1909) and his wife, née Mary Bridge Canedy (1826-1882), rented rooms in this “double house" from 1857-1861. According to their granddaughter, Annie Malcolm Slade (1878-1963), the Slades were also participants in the URR, locally. One story about the couple concerned the inquiries of a local sheriff about the Slades harboring fugitives. Mrs. Slade received him as a social caller and talked incessantly about everything but fugitive slaves. It was only after Mrs. Slade had escorted him out that he remembered the reason for his visit. The Slades were both school teachers, and Albion later became principal of the Fall River High School. In his youth, he worked on whaling ships to earn money to outfit himself for teaching.

Albion’s wife, Mary, a writer, was at one time an assistant editor of The New England Journal of Education, and the founder of Wide Awake, an organization which actively campaigned for the election of Abraham Lincoln. She also wrote a number of gospel song texts for Rigdon McCoy McIntosh (1836-1899), a well-known southern church musician (aka Emilius LaRoche).

Nathaniel Briggs Borden House, 40 Second Street (demolished)

Nathaniel Briggs Borden (1801-1865), who was lauded for his “naturally happy, cheerful disposition” and “large heart and generous sympathies,” was a wealthy businessman and politician, and served as Fall River’s third mayor; in 1834 he founded an anti-slavery society in Fall River. His third wife was Sarah Gould Buffum (1805-1834), the Quaker daughter of Arnold Buffum. The couple, who possessed strong abolitionist sympathies, opened their home to fugitive slaves and assisted countless others “either directly or indirectly on their way to Canada and freedom.” According to Edward S. Adams, the “station most frequently alluded to in Fall River” was the Borden residence.

The house, which was razed in the 1930s, survived the Great Fire of 1843, and was situated nearly opposite the spot where the fire began.

Fall River Historical Society, formerly Andrew Robeson Jr. House, 28 Columbia Street

In 1842, Andrew Robeson (1787-1862), a prominent New Bedford businessman, presented a two-acre lot of land on the south side of Columbia Street to his son, Andrew Robeson Jr. (1817-1874), and his daughter-in-law, née Mary Arnold Allen (1819-1903), as a wedding gift. The next year, a “mansion house” was constructed on the site; built of native granite, it was situated on the boundary line between Massachusetts and Rhode Island, with three quarters of the residence situated in the former, and one quarter in the latter.

The elegant residence included a wine cellar, which Robeson is reputed to have converted for use as a secret room for the concealment of fugitive slaves. Entrance to the room below was accessed via a doorway concealed behind a false panel of books in the library. The role of the house as a station on the URR was later carried on by a subsequent owner, “Friend" William Hill Sr. (1799-1881), a Quaker abolitionist, who purchased the property in 1854.

In 1869, the residence was sold to Robert Knight Remington (1826-1886), and was moved to its present location at 451 Rock Street, at which time it was enlarged and redecorated. The false bookcase panel, however, remains in situ.

Dr. Isaac Fiske House, 263 Pine Street

Dr. Isaac Fiske (1791-1873) was involved in anti-slavery activity in Fall River. At a Citizens Meeting in 1854, Fiske was among the signers of a resolution decrying the return of Anthony Burns from Boston “to the land of whips and chains…." Dr. Fiske’s son, George Robinson Fiske (1837-1918), was also active in the abolitionist movement. As a young man, George was active in the Wide Awakes, a group of young Republicans who campaigned for the election of Lincoln.

In February and March, 1939, a series of articles by Edward S. Adams, “Anti-Slavery Activity in Fall River," was published in the Fall River Herald News. One of Adams’ informants was Mrs. Dr. Howard Perry Bellows, née Mary Anna Clarke (1851-1946). Mrs. Bellows was Dr. Fiske’s niece and cousin to his children, George and Anna Robinson Fiske (1845-1929), later Mrs. Harry Theodore Harding.

According to Adams, Mary Anna Clarke was often warned by her older cousin, Annie, that “it was not safe to go into the attic, for there might be a runaway slave up there."

In her 1927 personal reminiscence, Annie referenced a Henry “Box" Brown (c.1816-1897). Brown was a well-known fugitive. Her testimony suggests an overwhelming possibility that Mr. Brown was indeed a guest in Isaac’s home. Brown, while still a fugitive, was a fixture on the Anti-Slavery lecture circuit between Providence and Boston, an itinerary that may have included Fall River. Whether the Fiskes aided Brown on his initial flight to Boston via New York remains unknown.

Who was Henry “Box" Brown?

Prior to the Civil War, Brown worked in his master’s tobacco factory in Richmond, VA, along 150 other slaves and free blacks. When his wife and children were sold and shipped from Richmond, he became determined to escape. Brown had collaborators and a plan was formulated to ship Brown from Richmond in a box three feet long and two feet deep. The plan was almost aborted, but the box was eventually shipped from Richmond to Philadelphia, PA, on March 13, 1849. Twenty-six hours later, at six in the morning, the crate, bearing a misleading address, arrived at the Anti-Slavery (Philadelphia Vigilance) Committee. While involved in Anti-Slavery activity in Providence, RI, Brown was twice nearly seized by agents there, which led to his seeking refuge in England to wait out the outcome of the Civil War.

Local historical sources on the Underground Railroad in Fall River

Most of what we know about the Underground Railroad in Fall River is drawn from four sources. One is a series of articles published in the Fall River Herald News from February 27, 1839, to March 11, 1839. These articles, collectively known as “Anti-Slavery Activity in Fall River," were based on a Fall River Historical Society paper written by Edward S. Adams, son of the URR conductor Robert Adams. Another source is Two Quaker Sisters, published in 1937, based on the original diaries of Elizabeth (Buffum) Chace and her sister Lucy Buffum (1829-1882), the wife of Rev. Nehemiah Gorham Lovell, with an introduction by Malcolm Read Lovell (1889-1975).

The first part of the book is Lucy Lovell’s domestic diary, but the second part is Mrs. Chace’s contribution to the record of the URR in Fall River, entitled, “My Anti-Slavery Reminiscences." In it, she describes the roles that Borden, Adams, and others took in assisting fugitives fleeing from slavery. Documentation of the actual routes can be found in Wilbur Seibert’s The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts, a lecture given before the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, in 1898. This lecture was published nearly forty years later as a 70-page pamphlet by the American Antiquarian Society in 1936.

THE RECOLLECTIONS OF ANNA (ROBINSON) FISKE HARDING (1845-1929)

This previously unpublished manuscript, a copy of which is housed in the Fall River Historical Society’s Charlton Library of Fall River History, was written in letter form by Fall River, Massachusetts, native, Anna Robinson (Fiske) Harding, and addressed to her children and grandchildren, who she affectionately referred to as “My Dears.”

Anna was the daughter of Dr. Isaac Fiske (1791-1878), a homeopathic physician in Fall River, and his wife, née Anna Robinson (1808-1887). The erudite couple were devout members of The Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers, were “great reformer[s],” and actively participated in the Anti-Slavery movement, being interested in all good causes. The Fiske residence at 49 (later 263) Pine Street was a station on the Underground Railroad, where fugitive slaves often found refuge.

Anna’s reminiscences provide a rare glimpse into the private world of an enlightened, nineteenth-century Quaker girl who, admittedly, never knew what “surprises” she might find upon returning home to from school on “the noon hour.”

Stettler, Alberta, Canada

June 2nd, 1927

My Dears,

I want to tell you about something which occurred way back in the early thirties of the last century (1800).

Two men, Uncle and Nephew – [Dr.] Isaac Fiske [1791-1878], and [Dr.] John L[ewis] Clarke [1812-1880], went to attend [a] Friends’ Quarterly Meeting at East Greenwich, [Rhode Island], out of Providence, [Rhode Island]. They sat in the gallery, and tho’ plain in dress, they must have had an eye for a pretty girl, for they soon discovered two young ladies sitting on the main floor, who looked very attractive in their close cottage bonnets. So when Meeting was over, Isaac and John lingered outside until the maidens came tripping by.

They were dressed alike in white muslin tucked to the waist, belts, cuffs, bags, and little capes of maroon-colored velvet, and with white bonnets enclosing two lovely faces. They were the two “pretty Robinson sisters,” Anna [1808-1887] and Mary [1811-1900]. [The girls were the daughters of Gideon Robinson (died 1817) and Patience Davis (1786-1854), later, Mrs. Oliver Chace].

The one with clear olive skin, glossy black hair, and beautiful soft black eyes; and the other a pink and white beauty, with blue eyes and delicate soft skin. “Thee may take thy choice, John,” said Isaac, but he afterwards chose for himself. They were introduced – he [Isaac] took Anna for a drive, and in three months he and Anna were engaged. These were my father and mother. [They were married in Swansea, Massachusetts, on October 7, 1835.]

And later on, [in Swansea, Massachusetts, on June 11, 1840, Dr.] John [Lewis Clarke] married Mary [Robinson], and they were Cousin Mary Bellows’ parents [Mrs. Dr. Howard Perry Bellows, née Mary Anna Clarke (1851-1946)].

Anna and Mary had attended Friends’ Boarding School [Moses Brown School] in Providence, [Rhode Island], and both held Certificates of high standing. This institution still exists and is among the best in every respect. The daughter of the Japanese Ambassador to the United States, living in Washington, [District of Columbia], attended the Friends’ School last winter. [Princess Chichibu Setsuko, née Setsuko Matsudaira (1909-1995), the daughter of His Excellency Tsuneo Matsudaira (1877-1949), Japanese Ambassador to the United States 1924-1928, attended the Sidwell Friends School, in Washington, D.C., from 1925-1928.]

[My] brother, George [Robinson Fiske (1837-1918)], was the first child born to the Fiskes, then came two little boys who both died, [Isaac Gideon Fiske (1838-1840) and Isaac Fiske, Jr. (1841-1843)] and then Anna Junior [the author of this paper, Anna Robinson Fiske (1845-1929)] came on April 8th,1845.

She grew and grew, and grew, until she became a young woman, and then she married [in Boston, Massachusetts, on June 20, 1876], Harry Theodore Harding [1849-1933], of Windsor, Nova Scotia, and lived ever so many years before she thought of jotting down some of her old memories, which might be of interest to you all.

In my Father’s house [49 (now 263) Pine Street, Fall River, Massachusetts], everything relating to Queen Victoria [1819-1901] was always read aloud, so she became a notable and beloved personality in the family, and I think this helped to influence me in regard to leaving my own dear country and coming to reside under Her dominion. That, and dear Grandfather’s winning ways!

You must understand that after “the most straightest” of their sect, Isaac and Anna were [members of The Religious Society of] Friends, and their family life was quite different from anything you know about. Everyone not a Friend, belonged to “the World’s people,” and while pitied and prayed for, must not in any sense be copied. Musical instruments were not allowed in any Friend’s house, and no instruction in singing or piano playing encouraged or even permitted. Father was really fond of music at the bottom of his heart and one evening four of the Clarke Boys (Uncle John’s brothers) were at our house, and I was awakened out of a sound sleep by their singing, as a part song, “Oft in the Stilly Night” [by Thomas Moore 1779-1852]. I really thought I must be in Heaven. [The Clarke brothers were: Erasmus Darwin Clarke (1815-1987); Isaac Weeden Clarke (1819-1884); Horace Clarke (1823-1904); and George Augustus Clarke (1830-1866).]

The Society of Friends came to the fore in England, when there was so much extravagance and gaiety at Court, and in society, and did a valuable work in helping to restrain the mad lust for revelry, but the manner of life of “the most straightest” made it very hard for little Anna [the author of this paper], on account of the rigid rules which conscience demanded of parents. Plain colors, plain living, and conversation, and of course, in addition, strict regard for honor and integrity underlying all. But little Anna liked bright colors, and wanted story books, with pictures, such as she saw in shop windows, which were all forbidden. Willie Lyon [Rev. William Henry Lyon, DD (1846-1915)], a neighbor boy, [who was] afterwards a noted preacher [at Christ Church] in Brookline, Massachusetts, once gave her, on the quiet, two story books to read – one, The Ugly Duckling [by Hans Christian Anderson (1805-1875), published in 1843], and the other The Fairy Prince, and these two are all she can remember having seen.

In a closet in the upper spare room [of our house] was a picture of George Fox [1624-1691], the founder of The [Religious Society of] Friends, and I can remember getting it down and kneeling before it, and saying, “Oh George, why was Thee ever born, to make little girls so miserable?” But George’s solemn face did not change, and boded no indulgences to worldly-minded little girls, so with a heavy sigh he was replaced on the shelf, and the door closed.

But my Father and Mother were the tenderest and kindest of parents, and did everything possible to lighten and brighten my days for me. And after I went to school I invented the most wonderful method of brightening up my own person. At that time, just as at present, ribbons and bows were worn by girls. We had a lovely fruit garden, and for a choice bunch of grapes, or a cluster of black English cherries, I could purchase the loan of a fancy ribbon to wear during school hours. My Father was a [homeopathic] physician in Fall River, Massachusetts, and the highest price I ever paid for anything was a bottle of pills (unmedicated), for an afternoon’s wear of a white apron with bows on the shoulders and pockets; lessons took on an added glory from the adornment of my small person, but if the mothers of the parties to these transactions could have seen us, what would have happened? But the Fates were kind.

Exciting days at the house would come around at “Quarterly Meeting” time, when Friends would gather from surrounding towns to attend this function. Our hall, a large one, would be stacked with tall drab beaver hats, and umbrellas, [and] with valises; and hat rack, tables, and chairs [were] covered with plain bonnets and shawls, while cups of tea and ginger cakes (for which my mother was noted) would be passed in the living rooms ad libitumto, to the serene, smiling, benevolent-faced visitors who accepted my Father’s hospitality. Still, we younger ones kept an eye to the windward, for we never knew just when this assembly might resolve itself into a “Sitting,” and the voice of prayer or exhortation be raised in our midst, as the “Spirit” might move.

We were too young to appreciate the significance of this belief in the ever-present Spirit, which might at any time force itself to be actively regarded, but no doubt much of the saintliness of the old-time Quakers was due to their constant and abiding communion with the Holy Spirit.

My father was a great reformer and [an] anti-slavery, women’s suffrage, prohibition man, [and] all these objects held his sympathy and consideration. The noon hour, when I came home from school, held many surprises for me. There might be an escaped slave at the house, on his way north to freedom in Canada, (whose presence must be mentioned with bated breath). The famous “Box Brown” [Henry ‘Box’ Brown (c.1816-1897)], who escaped [on March 29, 1849] from the South [Richmond, Virginia] in a big packing box, [labeled] as freight, being one of these.

The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison’s Anti-Slavery newspaper, [published from 1831 to 1865] was read often in the family, and the wrongs of the poor slave were a never ceasing sorrow and regret, and subject for prayer. Those were the days when the Woman’s Rights movement began, and one day I came upon a very strange looking person in my father’s office, in earnest conversation with him and mother! Was it a man? Could it be a woman? Ah, yes, one of the pioneers of the principle, all the way from Chicago, [Illinois]. Lucy Stone Blackwell [Mrs. Henry Browne Blackwell, née Lucy Stone (1818-1893)] in bloomers! The costume did not appeal to me – it was not attractive, and for many years I recall antipathy to “Woman’s Rights” dating from that time. Riper judgment however, teaches that the pioneer must of necessity advance far beyond the masses. The army does not advance until the scout has marked out the way; and all honor to those who march fearlessly forward, far, far, in advance of a carping public, which, after all, is only too ready to take advantage of all the gifts thus provided.

Those years in the [eighteen] fifties, were just bubbling and boiling over with reforms without any let up, just as at the present day we are overwhelmed with so many scientific wonders and benefits.

To go back a little – among my earlier recollections outside of home, one day I was taken by Father and Mother for a walk down by the wharves – most unusual! To be allowed to see so many queer and interesting places! Many citizens were pacing up and down or standing in groups, and men with set faces were looking after chests and luggage, which were being loaded on to a vessel at the dock. It was easy to see this was no ordinary gathering, this sad, anxious-looking assembly. After a time, the baggage was all shipped, fond “Goodbyes” and “God-bless yous” were exchanged, a company of sober-faced men sprang on board, and while tears rained down many a cheek, the ship cleared the docks, sails were hoisted, and the “Forty-niners” from our city and district had started on their long voyage round Cape Horn to the gold fields of California.

It was in this year [1849] also that the epidemic of Asiatic cholera [the so-called ‘second cholera pandemic,’ lasted from 1829-1849] prevailed and made such fearful ravages among us. Terror was abroad, for no one knew what house might be visited next by this terrible scourge, and many a home was robbed of its brightest and best. Child as I was, I well remember Father’s accounts of the stricken ones during his ministrations among them. The agony and anguish of the doomed was frightful. A maid in our home had a very light attack of it. I did not know what was the matter, but was told on no account to go near her. However, one day I heard her calling “water, water, for God’s sake, water!” I quietly took up a glass to her, and can well remember the ferocity with which she gulped it down. Water was only allowed in the smallest quantities by the M.D.s. No evil resulted from my well-meant, but dangerous attentions, and no one else in the house took the disease.

I remember also a very bad scourge of small pox in Fall River. Vaccination was not sowidely practiced then, and the attacks more virulent. Science here again has done so much to alleviate.

As a rule, children take the Bible literally, and I was no exception. My Father read one day the passage “When thou prayest enter into thy closet” – well, I hadn’t any closet really my own, but the big sofa was slightly across the corner in the living room, and I went behind it and knelt down and said my little prayers there, and I felt confident that He who said “Suffer little children to come unto Me,” heard that petition.

As a family we were extremely fond of animals, horses, dogs, and cats, and could not understand how many people cared so little for them. My first knowledge of French was a little phrase Father taught me: “Mon petit chat, Je vous aime – M’aimez vous?” (My little kitten, I love you – do you love me?)

Uncle George was one of the dearest and kindest of brothers, and I worshipped the ground he trod on. He was seven years older than I, and when he became a banker, was able to help me out in many ways that Father’s conscience would not have allowed him to do. His opinions were almost a law to me, and he made a very large place in my life then, and as long as he lived. [George Robinson Fiske, died in Boston, Massachusetts, on August 18, 1918].

When I was in my teens, New England was swept by a wave of lecture-bureaus and seasons, and Father and Mother would take me with them to hear these notable men.

James Russell Lowell [1819-1891], Ralph Waldo Emerson [1803-1882], Wendell Phillips [1811-1884], William Lloyd Garrison [1805-1879], Charles Sumner [1811-1874], Mark Twain [1835-1910], [Francis] Bret Harte [1836-1902], Louis Agassiz [Jean Louis Rodolphe Agazziz (1807-1873)], and others, as well as many English speakers of high renown, and the sayings of these men became household words in the family.

Agassiz was shy when he began to speak, but when warmed up to his work would hold an audience breathless with the wonders of the earth which he expounded to them, and Wendell Phillips [1811-1884], “the silver tongued orator”, was a joy to hear – Oh, they were all excellent, and it meant a liberal education to hear them.

Cousin Mamie Clarke [Mary Anna Clarke (1851-1946), later Mrs. Dr. Howard Perry Bellows] and I grew up together like sisters, although her parents having left the [Religious Society of] Friends, made her early life quite different from mine, and Cousin Eloise Davis was another sister to me always and my yearly visits to New York, were a delight and an education.

Pictures, music and the plays there were the best in America, and one heard: Parepa Rosa [Euphrosyne Parepa Rosa (1836-1874), a British operatic soprano]; Ole Bull [Ole Bornemann Bull (1810-1890), a Norwegian virtuoso violinist and composer]; Marie Anderson [Mary Antoinette Anderson (1859-1940), an American stage actress]; Edwin Booth [Edwin Thomas Booth (1833-1893), an American stage actor]; Salvini [Tomasso Salvini (1829-1915), an Italian stage actor]; Christine Nilsson [Christina Nilsson, Countess de Casa Miranda (1843-1921), a Swedish operatic soprano]; and others, and every year the Picture Galleries had a new masterpiece on view.

I must relate an event that is still etched in my memory as if on copperplate. One beautiful morning [April 16, 1865], I was moving about in my room – the air soft and warm and the whole world apparently at peace, when suddenly a church bell began to toll – then another, and another, and another, till the whole world seemed filled with grief. And so it was, for I overheard a man on the street say to another, “President Abraham Lincoln has been assassinated!” [Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), the 16th President of the United States, was assassinated on April 15, 1865.]

What a wave of sorrow swept over the land at this unmitigated horror! A martyr to his love for freedom, and one who could never be replaced.

His wife [née Mary Ann Todd (1818-1882)] also suffered with and for him. The May number of Cosmopolitan [Magazine] for 1927 contains an article, “The Unhappy Story of Mary Todd – the Woman Lincoln Loved: Told to Right a Great Wrong,” by Honoré Willsie Morrow [nom de plume of Nora Bryant (McCue) Willsie Morrow (1880-1940)].

She was a Southern woman of good birth, well-educated, and an accomplished linguist, but her marriage [on November 9, 1842] to [Abraham] Lincoln made her a fair mark for the venom of his enemies. Charles Sumner [(1811-1874), an American politician and senator] was always her warm friend, but even he could do little for her – the anger against Lincoln for having freed the slaves was so intense. [The Emancipation Proclamation, went into effect on January 1, 1863].

After his tragic death she was still a martyr to calumny, and even lived in poverty, suffering for his sake and for the cause for which he died.

Fall River, [Massachusetts], having a natural water-power [the Quequechan River], made it an ideal place for mechanics, and after the Civil War, many cotton mills were built and run there, and people made very large fortunes thereby. The first party I ever went to was an immense coming-of-age reception [held in June, 1864, to which 1256 guests were invited] of Matt Durfee [Bradford Matthew Chaloner Durfee (1843-1872)], a chap worth about $15,000,000, which in that day ranked about as high as Ford’s or Rockefeller’s fortunes do now [in1927]. Supper was served in a very large marquee tent [erected on the grounds of his North Main Street mansion], Mendelsohn’s Quintette Club from Boston, [considered the most active and widely-known Chamber Music ensemble in the United States, from 1849 to 1895,] played during the evening in the house, while [a] military band was stationed outside on the [extensive] grounds, which were all lighted up with Chinese lanterns.

In the winter the same Matt Durfee took a party of us down to Newport, [Rhode Island,] in his drag, on runners [a carriage with side seats that could accommodate twelve passengers, with a door and steps at the rear, and a high seat for coachman and owner], with four horses [Percheron Stallions; the drag was driven by William Jeff (1843-1912), Durfee’s coachman,] to attend a [United States Navy Training Academy] Midshipman’s’ ball there. This was my first dance, and we stayed at one of the large hotels and had what we thought was a good time! The training ship was then stationed at Newport, and the man who led the cotillion at the dance was Matt’s cousin, [possibly Matthew Chaloner Durfee Borden 1843-1912]. So you see, Grandma had much gaiety and variety in her life after leaving school – so much so that it was easy to go to the more quiet Nova Scotia, and afterwards to take up the privations of pioneer existence in this wonderful Alberta.

My mother was always the dearest and kindest and most competent of parents. Father died [in Fall River, Massachusetts, on June 2, 1873] before I was married, so she became one of our family in Nova Scotia. She had a very sweet smile and charming manner, and made friends everywhere, and I always felt safe in meeting so strangers, for there was Mother! She was my sponsor! She and my dear husband were always the warmest friends, and in her dying hours among her last words were these, “Harry, Thee has been a good son to me”. A high and most loving tribute to his character. [Anna (Robinson) Fiske died on December 27, 1889.]

Alberta [Canada], is a province of great promise and we have made a home for ourselves here. We are most fortunate in having Henry [her son, Henry Fiske Harding (1878-1963)] with us, or near us, but it is a great sorrow to be so separated from all you dear ones, so far removed from us, and husband and I often regret that we cannot look more frequently upon your beloved faces.[In addition to Henry, the Harding children were: George Theodore Harding (1879-1965); Louis Harding (1880-1933), and Eloise Harding (1888-1950), the wife of Archibald Wilson Pride.]

We are both nearing the time when man goeth to his long home and our hopes and prayers are that, until we meet in Heaven above, God will bless You, one and all, and keep you safe in the hollow of His hand. [Anna Robinson (Fiske) Harding died on December 22, 1929; her husband, Harry Theodore Harding, died on January 5, 1933.]

And so, my dear ones, “say not goodnight, but in some brighter clime, bid us good morning.”

Anna [Robinson Fiske] Harding