Lewis Howard Latimer: Inventor & Patent Draftsman

by Dr. Stefani Koorey

Lewis Latimer was born on September 4, 1848, in Chelsea, Massachusetts, the youngest of four children of George Washington Latimer (1818-1896) and Rebecca Smith Latimer (1822-1910).

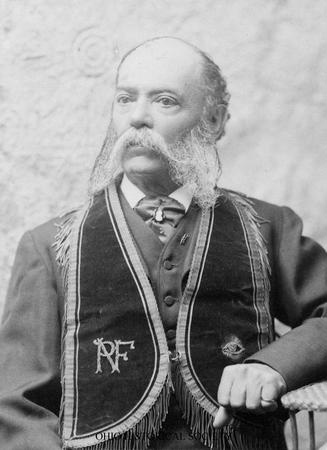

GEORGE WASHINGTON LATIMER

George Washington Latimer was well known during his lifetime and his daring story of his escape from slavery inspired many prominent people before the Civil War. He “was the first fugitive slave whose emancipation guided and influenced the American abolitionists of the 1850s. His flight to Boston, arrest, imprisonment, trial, and emancipation, as well as the numerous public meetings held all over Massachusetts on his behalf, made his a cause célèbre, fifteen years before the famous Dred Scott Decision.” (Davis, “The George Latimer Case”).

George had grown up in Norfolk, Virginia, the son of a white stonemason, Mitchell Latimer, and Margaret Olmstead, a slave owned by Mitchell’s brother Edward. The first sixteen years of George’s life were spent as a house servant for Mr. and Mrs. Edward Mallery (Mrs. Mallery’s first husband had been Edward Latimer). Apparently, George was well treated and allowed to hire himself out “as long as he paid a quarter a day for food, clothing, and shelter” (Fouché, Inventors in the Age of Segregation). When financial times were hard in the 1830s, his freedom to work for himself ended and, over the next eight years, George “was hired out, jailed for the Mallery’s debts, sold several times, and generally mistreated” (Fouché).

Because of his dire circumstances, in 1840, George escaped his captivity, only to be captured and returned. He ran away again in October of 1843, but this time took his wife Rebecca Smith, whom he had married in January of 1842, and who was pregnant with their son George Jr.

According to the book Lewis Latimer, co-written by his granddaughter Winifred Latimer Norman and Lilly Patterson:

On October 4, 1842, Rebecca and George Latimer slipped onto a steamer at Norfolk and hid nine hours in the darkness of the ship’s hold. When the vessel reached Baltimore, they used their railroad tickets [which George had saved for] to travel to New York. Being fair skinned, George posed as a Virginia planter, and Rebecca played the role of his servant. Four tense and exhausting days of travel later, the courageous couple reached the free state of Massachusetts. George chose to go by the name of Latimer, vowing that in freedom he would bring honor to the name of his father.

Unfortunately, the couple ran into a man who worked for George’s master after their arrival in Boston. His slaveholder, James B. Gray, a shopkeeper, appeared in Boston on October 18 to reclaim his property. George was arrested.

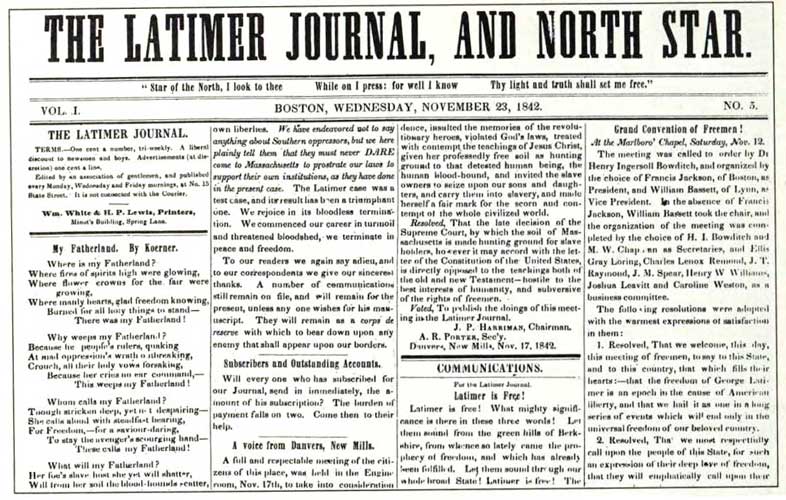

In this short space of time, George gathered the support of many of Boston’s most notable abolitionists, such as Dr. Henry Bowditch, William Francis Channing, Frederick Cabot, and William Lloyd Garrison (Fouché). Working together, the group had published six issues of the abolitionist paper The Latimer Journal and North Star, which publicized George’s plight. After several weeks of incarceration, during which the excitement of the public in his favor grew, George was manumitted on November 18, when a Black minister, the Reverend Samuel Caldwell, minister of the Tremont Temple Baptist Society, raised $400 and paid the attorney representing James Gray for his lost property.

George Latimer used his new-found notoriety to attend abolitionist rallies, conventions, and meetings throughout the area, speaking about his experiences and the evils of slavery. He says he appealed “for signatures to the famous ‘Latimer’ petitions, to be presented to the Legislature and to Congress. These asked the respective bodies to erase from the statute books every enactment making a distinction on account of complexion, and the enactment of law to protect citizens from insult by alleged arrest” (Davis).

“In 1894, Frederick Douglass wrote to Lewis Latimer about the impact his parents had on Northern abolitionists after their freedom was won. Douglass stated that one ‘could hardly imagine the excitement the attempts to recapture them caused in Boston. It was a new experience for the Abolitionists and they improved it to the full extent capable.’ … [Lewis, thus] saw his father as a valuable participant in the fight against slavery. … He saw many whites as benevolent citizens working for the betterment of an underprivileged race” (Fouché) and did not grow up experiencing the white population as a malevolent foe.

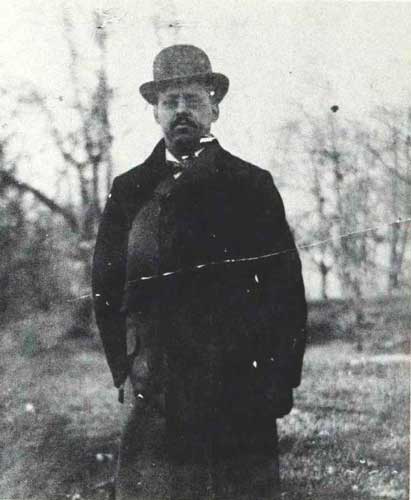

LEWIS LATIMER

Lewis Latimer’s early years were quite normal, attending Phillips Grammar School and secondary school in Chelsea. He assisted his father in his barbershop, which was a well-respected business for Blacks in the nineteenth century. George’s father additionally had secured employment as a paper hanger, and Lewis helped him there as well.

In 1858, when Lewis was ten years old, his father left his family. According to Dr. Philip T. Silvia Jr., George’s “new residence was the state prison at Charlestown [Massachusetts] where he was incarcerated, whether justly or not, after having been found guilty on a breaking and entering charge” (Silvia, “Sarah Anna Lewis”). He was never to be reunited with his family but, according to Fouché, George had stayed in the area and was sighted by Frederick Douglass in Boston in later years, who wrote to Lewis about his encounter.

Without George’s income, the family was now in severe financial straits. Rebecca could no longer afford to care for George Jr, Margaret, William, and Lewis. While many sources claim that Lewis and his siblings were sent to a pauper’s “State Farm,” Fouché reports that in Lewis’s 1911 Logbook, he stated that because of their family’s situation, his “two brothers were sent to a state institution … the Farm School from here they were bound out.” George worked for a farmer, William for a hotel keeper, and Margaret was “taken by a friend,” probably as a house girl. Lewis, in fact, remained at home with his mother as he was too young to be sent to the Farm School.

By the time Lewis was thirteen, he was working as an office boy for an attorney “and became familiar with legal practices at an early age. After a stint waiting table for a Roxbury family, he secured a job as an office boy for Isaac H. Wright, a distinguished local attorney” (Fouché).

At the age of sixteen, Lewis lied about his age and enlisted for a three-year term of service in the Union Navy on September 16, 1864, and served briefly on the USS Ohio and later the USS Massasoit. While aboard the Massasoit, the gunboat patrolled the New England coast for Confederate raiders, participated in several escort voyages from New York City to Hampton Roads, Virginia, served picket duty on the James River in Virginia, and took part in the January 24, 1865, duel with Confederate batteries at Howlett’s House. Later, she took part in preventing any southern rams from reaching the coast and was ordered on April 6 to carry dispatches to General William Tecumseh Sherman in North Carolina.

Lewis served honorably and was discharged after nearly ten months on July 3, 1865 (the Civil War officially ended on April 9, 1865), in Boston. In short order, he found a position in the firm of Crosby, Halsted & Gould, Solicitors of American and Foreign Patents (later Crosby & Gregory). They had been looking for “a colored boy with a taste for drawing” (Fouché). John J. Halsted was a former principal examiner of the Patent Office, as well as a partner in the firm. It was while working there that Latimer acquired his drafting skills, carefully watching the other draftsman at work, and purchasing his own set of drafting instruments. Latimer would practice at home until he could replicate the work of the more experienced professionals. “This process of emulation, an informal apprenticeship, was the best training that many craft, technical and engineering people received in the nineteenth century” (Fouché).

When the draftsman at the firm left for another position, Lewis Latimer was appointed to fill the vacancy, and from 1866 to 1878, his income increased from $3 to $20 a week, a marked improvement on his standard of living. As a sign of the times, however, Latimer was paid $5 less a week than the white draftsman he was replacing.

Latimer’s duties were varied. He was responsible for “making drawings for, and superintending the construction of, the working models … required by the US Patent Office” (Fouché), performing patent research for the firm in the Boston area, all while having a firm handle on the technical and legal aspects of patenting.

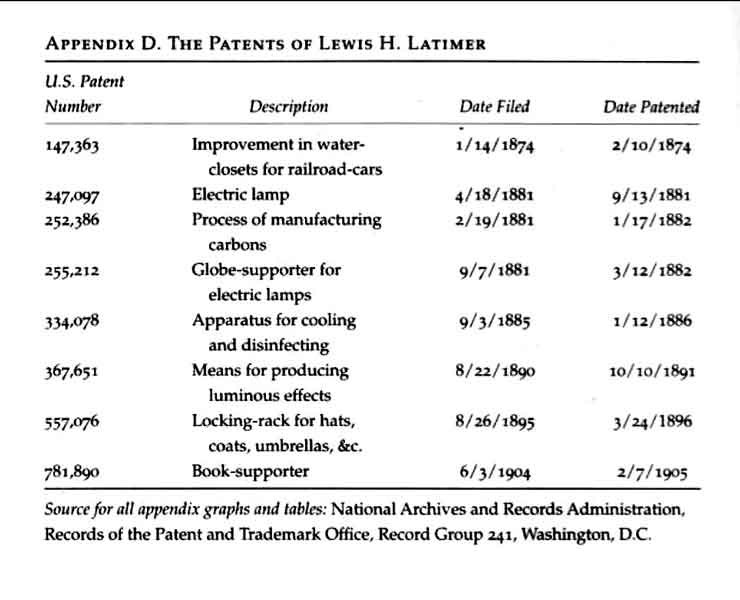

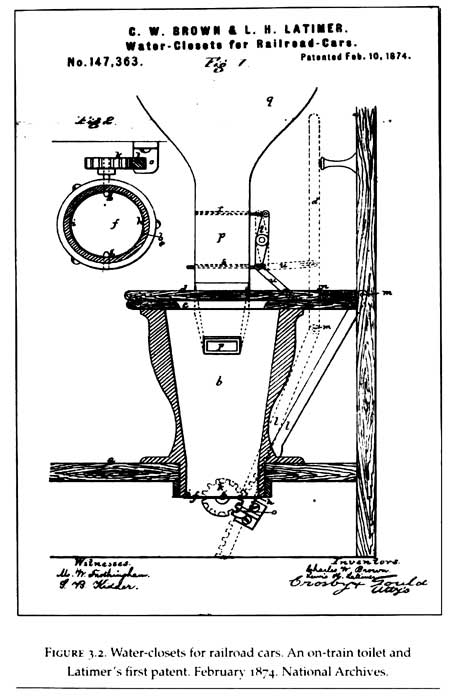

Latimer’s first patent was in 1874, an “Improvement in Water-Closet for Railroad-Cars,” copatented with Charles W. Brown. Says Fouché:

Instead of having a toilet opening to the ground, where ‘dust, cinders, and other matters [could be] thrown up from the track,’ Latimer and Brown devised a commode with a trap door activated by the toilet lid. They ‘constructed the apparatus with an earth-closet mechanism; by which a supply of dry earth, sand, or equivalent material is lodged upon the … receiving or discharging plate whenever the seat-cover is raised, and before the apparatus is used.’

Because Boston was one of the centers of electrical invention, it was through Latimer’s eleven-year tenure at Crosby & Gregory that he became conversant in electrical technology. By the mid-1870s, Latimer had drafted the drawings for the application for a telephone patent for Alexander Graham Bell. It is unclear if this was part of his duties at Crosby & Gregory or if he did this work on a freelance basis. Even though some historians have suggested that Bell asked for Latimer’s services, there is no evidence of this. According to Fouché, “It was merely that Latimer was the draftsman of the patent law firm that Bell retained to file his patent application which required Latimer to perform the final drawings.”

No research thus far* has revealed the actual event or circumstance that precipitated the introduction of Lewis Latimer to Mary Wilson Lewis (1847-1924), the woman who would become his wife. During the time of their courtship, Latimer was working in Boston for Crosby & Gregory and Mary was living in Fall River, Massachusetts. Mary’s sister was Sarah Anna Lewis (for details, please see this biography), the first Black person to graduate from the State Normal School in Bridgewater, Massachusetts (later to become Bridgewater State College), a prominent teacher’s college.

Lewis Latimer and Mary Wilson Lewis were married in Fall River on November 15, 1873. Their marriage lasted over fifty years.

Managerial changes at Crosby & Gregory, and Latimer’s inability to find agreement with the way Gregory did business, resulted in Latimer resigning his position in 1878. He soon found a similar position with Boston patent solicitor Joseph Adams. Unfortunately, “the adverse business climate” forced him to support himself as a painter and paper hanger. After a short stint working for the Esterbrook Iron Foundry in South Boston, his sister Martha and her husband Augustus Hawley suggested he move to Bridgeport, Connecticut, where she and her family lived. It was this decision that was to change Latimer’s life forever.

After moving to Bridgeport at the end of 1879, Latimer worked briefly as a draftsman at the Follandsbee Machine Shop. It was during his time there that he met Hiram Maxim, founder and chief electrician for the U.S. Electric Lighting Company, and inventor of the Maxim guns, which had become standard weaponry in the US and Britain.

Maxim was impressed by Latimer’s drawing talent and his work with Crosby and Gould, which had an excellent reputation, so he hired him only a week after being introduced. Latimer recalled, “I was installed in Mr. Maxim’s office busily following my vocation of mechanical draughtsman, and acquainting myself with every brand of electric incandescent light construction and operation” (Norman and Patterson).

Latimer made important social connections as well as expanded his expertise in the scientific and technical aspects of electric lighting. He wrote articles and gave lectures about recent science and technology and became a public voice in the electric light community. Regardless of his race, he had become “increasingly accepted by the corporate electrical culture that had a position of prominence in the development of electrical technology” (Fouché).

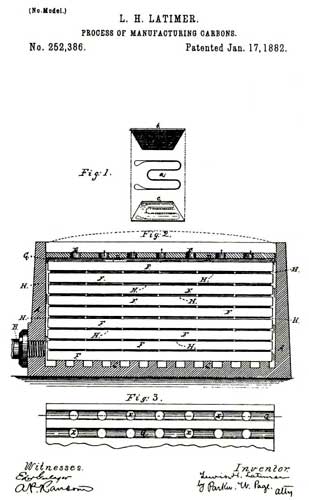

It was only a year before Latimer joined Maxim that Thomas Alva Edison had received his patent for the electric light bulb. But there was a problem with the invention: the carbon wire filament lasted only for a few days at the most, so it became expensive to use this invention as it needed to be frequently replaced. Of course, experts and inventors from around the globe worked to solve the problem. And who was the man who was able to figure it all out? Lewis Henry Latimer.

After conducting hundreds of experiments using differing methods and materials, Latimer succeeded by combining “previous manufacturing techniques with several new materials that allowed carbon filaments to last longer and to be made much more inexpensively.” Continues Norman and Patterson:

Latimer’s procedure involved stuffing blanks, or shapes, of such fibrous materials as wood or paper into small cardboard envelopes and thus exposing them to extremely high temperatures in an airless environment. He discovered that by coating the inside of the envelopes with a substance that kept them from sticking, or encasing the blanks between two strips of tissue paper, he could keep the blanks from welding to the envelopes. It was the cardboard envelopes that made Latimer’s invention different from existing filaments—and that made it work so well.

The company that Latimer worked for did not structure itself to build an entire electrical system, as the Edison Company had done. Instead, they focused primarily on the production of a quality incandescent lamp, which the owner, Hiram Maxim, was not optimistic about. With such extreme competition in the industry, most companies had small staffs. The U.S. Electric Lighting Company had only eight men working at their factory when they moved to New York City.

Because of Maxim’s waning interest, Latimer took on more and more of the responsibilities for the company’s survival. He participated in all of the lighting installations that were undertaken in 1880 and 1881, which included the Equitable Building, Fiske & Hatch, Caswell & Massey drugstore, and the Union League Club. According to Fouché, Latimer was solely in charge of operations and when the company “expanded its operations to Philadelphia, Latimer was one of the valued men brought along to assist in the implementation of a lighting system in the Philadelphia Lodger Building.”

Latimer’s biggest achievement, however, was the installation of several lighting systems in Montreal, Canada, around the middle of 1881. He was most successful with his dealings with the French Canadian workers as he learned the language in order to communicate instructions effectively.

Latimer continued to invent products that proved fundamental to the development of the U.S. Electric Lighting Company, including a patent for an improvement in incandescent lamps in 1881, a patent for the “Process of Manufacturing Carbons” in 1882 (with Joseph Nichols), and a new type of globe supporter for arc-lamps in 1882 (with John Tregoing).

According to Fouché, “By the summer of 1881, Latimer had become the superintendent of the incandescent lamp department of the United States Electric Lighting Company. In this capacity, he directed the production of filaments, commonly known as carbons, for Maxim lamps,” and supervised forty men in the division.

In 1882, Latimer and his wife went to London so he could oversee the opening of a Maxim factory there. He finished the job ahead of schedule and when he returned there was no job waiting for him. With that, Latimer left Maxim’s employ in 1883. But less than a year later, he went to work for Thomas Alva Edison, joining the engineering department as a draftsman.

Writes Norman and Patterson:

Patents clearly played an important role in Edison’s work. His Edison Electric Light Company had been founded as a patent-holding company, which meant that the company’s success depended on its continued ability to acquire new patents. And the acquisition of patents depended on a detailed knowledge of the process of filing the forms properly at the U.S. Patent Office. … Edison needed a man such as Latimer. The 35-year-old black inventor knew the patent process inside and was well versed in electric lighting and power. In addition, he possessed self-discipline, patience, and was attentive to details. … Latimer quickly justified Edison’s faith in him. He tested and checked equipment, and he was put in charge of the company library. But a big part of Latimer’s job with the Edison Electric Light Company was to collect information that could be put into lawsuits concerning Edison’s patents. A number of inventors tried to capitalize on Edison’s work without his permission. It was Latimer’s role, as an expert on patents and electricity, to set the record straight.

In 1886, Latimer received a patent for an “Apparatus for Cooling and Disinfecting”—a device to make rooms cooler and cleaner. Other patents he secured were for a “Locking-rack for Hats, Coats, Umbrellas” for use in public places, and “A Book Supporter” to prevent books on shelves from getting bent out of shape.

In 1890, his book titled Incandescent Electric Lighting, A Practical Description of the Edison System was published by D. Van Nostrand & Company. It was wildly popular and was reprinted with additional content supplied by Latimer and several of his colleagues.

Latimer’s private life was filled with his artistic and literary endeavors. He was a poet and painter and even created portraits of his family, which included his wife and two daughters, Emma Jeannette (later Norman, 1883-1934) and Louise Rebecca (1891-1963).

Patent lawyer and engineer Edwin Hammer had been the chief technical assistant for the Board of Patent Control and was the unofficial historian of the Edison organization. On February 11, 1918, Edison’s 71st birthday, Hammer marked the occasion by gathering the twenty-eight charter members of the Edison organization, to which Latimer belonged. This select group became known as the Edison Pioneers and every year on Edison’s birthday, they would meet in Newark or the Menlo Park laboratory to celebrate. Latimer was the only Black person in this august body of inventors and engineers.

In 1922, at the age of seventy-four, Latimer’s career came to an end when his eyesight began to fail. According to Norman and Patterson, “He received a pension from the Edison General Electric Company of $17.50 a week, which was supplemented by a pension from the military of $72 a month.”

Soon after the Latimers celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary, Mary died. She was lain to rest in Oak Grove Cemetery in Fall River. Lewis was devastated by the loss of his wife and, after a stroke that left one side of his body paralyzed, he fell into a state of depression. In an effort to offer him solace and joy, a group of family and friends collected the hundreds of poems he had written over the years and had them privately printed on handmade Italian paper, bound as a book titled The Poems of Love and Life.

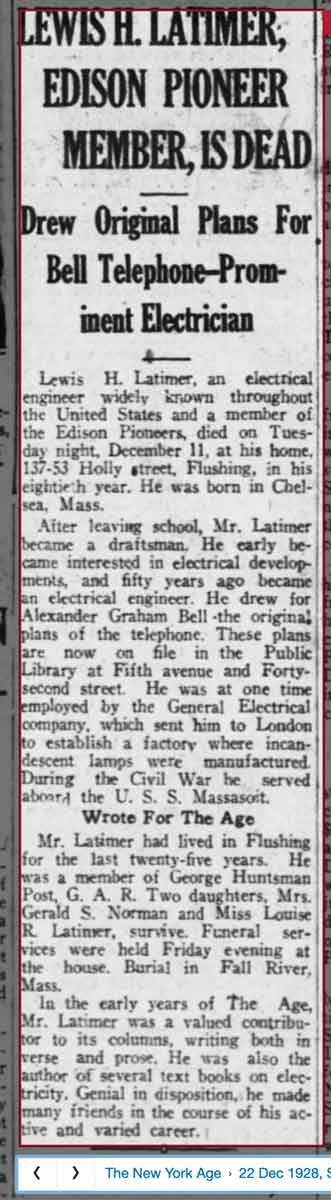

Lewis Latimer died three days later, on December 11, 1928. According to Norman and Patterson, “The Edison Pioneers were among those who paid tribute to Latimer, issuing a statement that said in part:

He was of the colored race, the only one in our organization … Broadmindedness, versatility in the accomplishment of things intellectual and cultural, a linguist, a devoted husband and father, all were characteristic of him. His genial presence will be missed from our gatherings.

He is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Fall River with his family, which includes: his wife, Mary Wilson (Lewis) Latimer; their daughter, Louise Latimer; mother, Louisa M. Lewis; Mary’s sister, Sarah Anna (Lewis) Williams; her husband, Edward A. Williams; and their daughters, Florence Rebecca Morgan and Harriet E. Pinkney. A simple headstone for Mary is all that adorns the plot.

In a recent turn of events, a new headstone will be placed on this grave on Saturday, September 23, 2023. It is a dedication and celebration of the life of this remarkable man. Read more about it in the Herald News here.

*This author has made inquiries to both the Lewis Latimer House Museum in Flushing, NY, and author Rayvon Fouché, who is now the Director of the American Studies Program at Purdue University, for some clarification on this issue. Neither the Latimer Museum nor Dr. Rayvon Fouché knew the answer. Additional contacts are being made with surviving Latimer relatives and any update will be reported, with edits to this biography made at that time.

UPDATE: The grave monument was installed on September 23, 2023. The day was rainy but it was beautiful event.

Sources: “Sarah Anna Lewis” by Philip T. Silvia Jr. (Bridgewater State College, n.d.); Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation by Rayvon Fouché (John Hopkins University Press, 2003); Lewis Latimer by Winifred Latimer Norman and Lily Patterson (Chelsea House, 1994); “The George Latimer Case: A Benchmark in the Struggle for Freedom” by Asa J. Davis (Rutgers University, Thomas A. Edison Papers).