Edison Electrifies Fall River by William A. Moniz

Electricity came to Fall River in 1883, and Thomas Edison himself helped flip the switch.

Electricity itself wasn’t “discovered” in the conventional sense. Instead of one transformational eureka moment there were many, spanning centuries of evolutionary development.

As early as 615 B.C., the Greeks described what we now know as static electricity by charging pieces of amber through rubbing. In the early 1600s, Englishman William Gilbert coined the word “electricity” from the Greek word for amber and described the electrification of many objects in his seminal work, De magnete, magneticisique corporibus.

As for founding father Ben Franklin, there are myriad patriotic reasons why his likeness graces the one hundred dollar bill, but he may be best known for somehow escaping electrocution while flying a kite in a mid-eighteenth-century thunderstorm; Franklin invented the lightning rod.

There were many other contributors: Alessandro Volta and his battery, André Ampere, and his magnetic coil, Michael Faraday and his electric motor, and Georg Ohm and his laws of current and resistance.

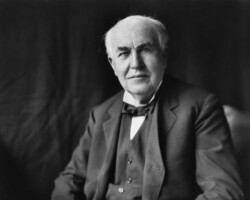

But the person most closely associated with modern electricity is Thomas Edison, who, although he was granted over one thousand patents in his lifetime, did not invent the light bulb. Rudimentary light bulbs had been around since at least the 1840s. But with the help of an 1874 patent design bought from Canadian inventors Henry Woodward and Matthew Evans, Edison perfected and patented the first practical light bulb in 1879.

Lewis H. Latimer, one of Edison’s researchers and a son of escaped Virginia slaves, is credited with creating an improved carbon fiber filament in 1882, greatly extending the life of Edison’s original bulb. Latimer had a local connection; he married Mary W. Lewis, a twenty-six-year-old Fall River seamstress in 1873. The couple died in the 1920s and are buried in Fall River’s Oak Grove Cemetery.

In 1882, Thomas Edison and his engineers were having problems perfecting his initial two-wire electrical distribution system employed at his Pearl Street demonstration plant in lower Manhattan, New York. The facility, serving fewer than one hundred customers and powering incandescent lighting only, was considered hazardous, having caused several employee injuries.

By the summer of 1883, while the Edison team continued to struggle with Pearl Street, what was to become known as the “Brockton Breakthrough” was taking shape. The newly-constructed Brockton, Massachusetts, plant introduced Edison’s revolutionary three-wire system incorporating a standardized and adjustable transmission grid. This more stable and efficient system proved that electricity could safely be transmitted to the general public from a centralized source. It soon became the prototype for generating systems throughout the country and the world, solidifying Edison’s fame and fortune.

In a move that would presage the mid-twentieth-century machinations of Madison Avenue pitchmen, Edison’s promoters decided to downplay the Massachusetts achievement. Shamelessly, they instead publicized the newly-outmoded Pearl Street plant to take advantage of the perceived economic benefits arising from a “first” centralized generating facility in more populous New York. To this day, Brockton’s unique role in establishing the country’s first three-wire generation and distribution system remains largely unrecognized.

In 1958, visiting Brockton on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the installation, Edison’s son Charles said, “In spite of the strong sentiment he felt toward the success of his ground-breaking work in New York City, Father always referred to his streamlined Brockton facility as his first complete model and his first showcase system.” Fall River was next.

Although several Fall River textile mills had installed stand-alone dynamos for lighting and for powering selective machinery, unlike Brockton, the Spindle City had yet to centralize electrification. That would soon change.

In 1883, two competing electric companies were formed: the Fall River Electric Light Company and the Edison Electric Illuminating Company with offices in the Borden Block. The latter company was associated with wealthy Fall River businessman Spencer Borden (Fall River Bleachery) who was Thomas Edison’s general manager for all of New England.

On September 26, 1883, Edison Illuminating Company Treasurer W.H. Dwelly wrote to Thomas Edison’s Engineering Secretary Samuel Insull requesting a construction quote. The letter reads in part—“Dear Sir: I learn from Mr. Borden that Mr. Edison is expected in Brockton the last of this week. That being so, I beg to suggest that he will bring the estimate for our Central Station with him and our Executive Committee will meet and consult with him regarding it.”

Nevertheless, according to The Phillips History of Fall River, The Fall River Electric Light Company was first out of the gate in March, 1883:

This company immediately leased land on Blossom Avenue, and constructed a generating station there. It did not then install any motive power for driving the generators, but purchased its power from a saw mill which was adjacent to the generating station. From the first this company supplied the City of Fall River with street lighting, and soon it began to serve stores with electric lights which were connected with the street circuits.

In late 1883, Thomas Edison came to Fall River to personally supervise the installation of the competing Edison Electric Illuminating facility. Visiting the city often over a period of six weeks, the Wizard of Menlo Park would stay and work for several days at a time.

During installation of the forerunner Brockton plant, Edison stayed at that city’s Hotel Palmer and his activities were widely reported. Unfortunately, little is known of Edison’s social activities and lodging arrangements while in Fall River, but it might be safe to speculate that many off hours were spent at Spencer Borden’s mansion on Rock Street.

One curious fact about Edison’s Fall River stay is known. According to Fall River Historical Society Curator, Michael Martins, Edison, who invented the phonograph in 1877, recorded the voices of several of the city’s prominent businessmen on tinfoil-coated cylinders as somewhat of a novelty. Designed to be replayed only once, a single artifact of Edison’s efforts remains in the Society’s collection: the unplayable, now folded tinfoil voice recording of David A. Brayton.

In 1892, electric power rolled up its sleeves for more than just lighting. On August 28 of that year, only two weeks after the infamous Borden Murders on Second Street, the following item ran in the Fall River Daily Herald:

TRIAL TRIP OF THE FIRST CAR ON THE NEW ELECTRIC RAILROAD.

The first trial of the electric street cars in the city was made yesterday afternoon from the Stafford Road barn to Rodman Street. The officials of the road were on the trial car when the power was turned on about 3 o’clock. From start to finish the trial was a complete success. The car was run uphill faster than it came down and it was started and stopped easily. The bell was clanged at every crossing and it attracted no end of attention.

Fall River’s formerly horse-drawn Globe Street Railway Company soon sold all of its stock except one. Snowball, the employees’ favorite, was lovingly cared for as a pet and mascot until its death in 1894.

By 1894, the two power companies were conveniently located adjacent to each other on Hartwell Street. In 1896, with demand for electricity quickly growing, the competitors decided to merge under the banner of The Fall River Electric Light Company.

By the turn of the century, the capacity of the combined Hartwell Street plants was nearing capacity. In 1906, a new generating plant with a capacity of 2500 kilowatts was completed on Hathaway Street. In 1917, with the new facility’s capacity already increased to over 14,000 kilowatts, several of the city’s mills decided to completely electrify their plants. The added source of power needed to accomplish this was achieved by connecting to the high voltage line that the New England Power Company had installed between Providence, Rhode Island, and Fall River.

In 1923, despite having installed further generating capability, the Hathaway Street station’s capacity was again at maximum. Rejecting further expansion of Hathaway Street as impractical, 1924 saw the company join with the Blackstone Valley Gas & Electric Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Brockton, Massachusetts, in constructing the Montaup Electric Company plant on the Somerset shore of the Taunton River.

The Fall River Electric Lighting Company (FRELCO) was reorganized into the New England Electric System (NEES), in the 1940s. In 2000, the company became part of what is now known as National Grid.

Thomas Edison’s breakthrough system, improved but fundamentally unchanged for 130 years, has gone from powering Fall River’s streetcars, light bulbs, and looms, to our TVs, cell phones, and laptops.

January 3, 2015,

Fall River, Massachusetts

EXCERPTED FROM: Granite, Grit, and Grace: An Exploration of the Fascinating Side Streets of Fall River’s History (Fall River Historical Society Press, 2017). Purchase your copy online HERE!