I was immediately interested when I saw the auction listing and accompanying photograph. It was a fine example of the artist’s work and attracted my attention.

Yes, very much so.

That interest, however, quickly morphed into surprise – intrigue, more like – when I saw the location of the auction house. A Dunning still life painting … in Australia?

Curious.

How, I wondered, did it get … there?

The listing:

Leonard Joel Auctions,

South Yarra, Australia

Lot 96

Robert Spear Dunning (American, 1829-1905)

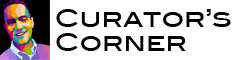

Still Life with Cherries 1882

Oil on canvas

Signed and dated verso: R. S. Dunning

Tilden Thurber Co. label verso,

24 x 34.5 cm

PROVENANCE:

Private collection

Private collection, Melbourne (bequeathed from the above)

Estimate $5,000 – $7,000 [AUD]

That estimate converted to $3,360 – $4,708 in US currency.

A reasonable estimate.

Yes, remarkably so.

The images that accompanied the listing evidenced that the painting had survived relatively untouched. It had clearly never been cleaned – the fruit was obscured by discolored, aged varnish and surface grime, and there was a frothy layer of accumulated dust in the recesses of the elaborate ornamentation on the frame molding – a good sign, that.

Why?

Because it had not been tampered with, at least not much.

There appeared to be a very small area of poorly done in-painting evident in the center field of the canvas, just above the cluster of grapes, and another to the lower right, but these appeared to have been added over the original varnish and layer of grime. An easy fix, that.

But still, despite the patina that obscured the painting, it glowed fairly through the murk, giving one a hint of what would be revealed when the curtain of the ages was finally lifted via treatment by a painting conservator.

It was lovely, really, and would be a fine addition to the FRHS collection – filling a gap in the museum holdings of Dunning’s work – and it would be nice to have it back in Fall River.

A homecoming of sorts.

There was a donor who had already provided the funds for just such an acquisition.

And so, the quest began.

Flashback:

Fall River, Massachusetts, 1882.

Robert Spear Dunning (1829-1905), the city’s preeminent artist, is in his South Main Street studio, with brush in dexterous hand applying the final touches to a painting.

Finis.

Well, perhaps not. A perfectionist, he was never fully satisfied and rarely considered a work complete.

The grand Borden Block – clothed in red brick and sandstone and imposing in its Ruskinian Revival grandeur – was Fall River’s leading business building, positioned on a choice corner lot in the heart of the bustling city center.

A plethora of rooms and office suites offering the most modern amenities of the era were available for hire throughout the structure that also housed the large and impressive Academy Theatre, its stage the second largest in New England. The third floor of the building was favored by artists. The studio located in the northeast corner of the building – large, airy, and bathed with the northern light preferred by artists for its consistency – was its optimum space. It was occupied by Dunning and his close friend, fellow artist and former student, Franklin Harrison Miller (1843-1911), the space divided by a privacy curtain that, according to contemporaneous accounts, was rarely drawn.

The perfume, as one approached the studio, would have been exhilarating to any true lover of art. Perhaps they paused, albeit briefly – as one should – to take in the sensory atmosphere, permeated with the scent of creativity. The aroma emanated from the materials used to bring artistic vison into reality, likely the products of England’s famed Windsor & Newton, for the inhabitants of the shared studio used only the best vehicles in their work.

It was a fantastic, slightly heady fragrance of oil paint squeezed fresh from tube to palette, of spirit of turpentine, and picture varnish – a concoction born of earthy pigment, of oil extracted from nuts and seeds, and the resins of nature.

There was likely the odor of smoke as well, that of some finely mixed tobacco wafting from pipe, cigar, or cigarette – Miller rarely denied himself the pleasure, and the toxins were even then feeding the cancerous cells that would one day cause his death.

The spacious studio shared by Dunning and Miller was a mecca for the artists, collectors, and aficionados.

And it was there that Lot #96 began its long and storied journey.

Down Under:

I have heard it said that Australians are nice people and I know this to be true, at least as far as the fine staff at Leonard Joel are concerned. They were fantastic to deal with – very helpful and accommodating to the extreme.

My questions about the condition of the painting and request for additional photographs – especially of the poorly done in-painting in the center field – were met with immediate response and photographic attachments via email.

A series of emails, in fact.

There were many questions that morphed into some friendly banter.

A condition report confirmed my initial observation: “Stable condition, with evidence of repair upper centre, and lower right.”

Yes, as suspected, the picture was virtually untouched; the areas inpainted were minimal, had been applied over the original varnish layer, and would be an easy fix.

And, yes.

The painting was, indeed, a very fine work. A stellar example of the brilliant, sometimes-minimal approach Dunning employed for still life.

It was painted in a straightforward manner with the fruit presented on a highly polished tabletop with an edge molding carved in an undulating motif; the mirror-like surface allowed for deep reflections. The composition was staged sans the elaborate trappings of crisp linen, fine silver, etched crystal, and porcelain tableware that he typically included in his paintings. Use of Victorian dining tables, groaning under the weight of elaborate serving pieces of myriad styles, beloved by affluent collectors who were Dunning’s patrons, was a penchant he habitually indulged in and the prevailing style in his works.

But not always, and definitely not in this case.

Choice fruit – one each of a peach, pear, apple, orange, and five cherries – is presented in a counterbalanced group around a large, luxurious cluster of green grapes, with each piece placed so that none repeats the position of another. The composition is bathed in warm colors and enhanced by the interplay of ambient light and shadow, with the glistening surfaces of various textures painted with the compelling accuracy that was a trademark of the artist.

The open, segmented orange – ripe and luscious – is painted in a manner reminiscent of an anatomical fruit specimen, a bravura tactic that allowed Dunning to fully exhibit his proficiency in rendering the contrasting textures of pebbled skin, pith, and juicy flesh. Dunning introduced the open orange into his still life paintings in the 1860s, and it was quickly copied by other artists of the Fall River School.

His technique was nearly photographic, the image captured not with lens but with brush and created using multiple, thin layers of glazing, with semi-transparent paints applied over the main color, producing rich, lustrous hues.

No finery of the well-dressed table in this composition, though, just fruit.

And a bountiful assortment at that.

Yes, it should be in the FRHS collection.

The Sale:

I very much enjoy estate sales and auctions, especially the previews – the thrill of the hunt. Exhilarating, really, and one never knows what might be discovered.

I am not, however, interested in the back-and-forth game of bidding at a live auction – never have been. I prefer a strategy whereby one waits until the bidding is seemingly done and then engages. Much simpler that way.

If I am unable to attend an auction, I always arrange to bid live via telephone. I hate the idea of online bidding, rarely use that platform – other than eBay – and chalk it up to my limited computer skills. Admittedly, I am an idiot when it comes to technology, and the fear that something could go wrong with my computer while executing a bid is always present.

What then?

Of course, it never seems to concern me that the telephone connection might just as easily be lost while bidding. In fact, the odds probably make that scenario more likely.

A personal idiosyncrasy, I suppose.

South Yarra, Australia, is in a time zone fourteen hours ahead of Fall River. I like my sleep and am a grouch when I do not get enough of it – miserable, really. Preferring not to bid in the middle of the night, I arranged an absentee bid executed by the auction house on behalf of the FRHS. The process is easy, and the house guarantees to bid at the lowest increment within a preset limit.

Simple enough, that.

And so, the wait began.

The sale took place on a Tuesday morning. Leading up to that day I often looked at the painting on my computer screen, scrutinizing it.

Yes, indeed, it was very nice.

Then, the second guessing began: Was the amount of the left bid sufficient? Had some other collector seen the painting? And what of the dealers?

Time would tell.

And it did.

The result:

Success. A hammer price of $4,600 [AUD]. That is $2,938 U.S. dollars – a very excellent buy, without doubt.

And so, a Dunning Down Under would return to Fall River.

Packing and shipping was easily arranged through the auction house and, remarkably, the crate arrived in Fall River within three days of being sent.

But what of the provenance?

How did it get … there?

The Provenance:

Provenance denotes the history of ownership of an object and is important in documenting a piece and helping to ensure that the current owner has a clear title to the object. Research forges new links in the chain of custody, sometimes all the way back to the artist’s studio.

Establishing provenance involves systematic, time-consuming investigation – it requires patience, expertise in research, and keen sleuthing skills akin to that of Holmes or Poirot.

In my experience it also helps to think like a prying old-maid – Miss Marple, for example.

Why?

Because establishing provenance often requires delving into other people’s business. You must uncover their identity, ideally make contact, and induce them to tell you something you want to know, but which they may not wish to divulge.

Suffice it to say that having had the pleasure – and, sometimes, not – of knowing many a nosey old maid in my day and thus privy to their techniques, I absorbed some of the skill. On the job training, so to speak.

One rarely forgets the teachings of childhood.

Documentation of provenance can come in many forms. Was the object mentioned in a letter, a diary, or an estate inventory? Is it accompanied by an invoice of some sort, a conservation report, or an old appraisal? Was it included in prior auction sales or listed in an exhibition catalogue? Are there inventory numbers or labels present?

Oftentimes, a wealth of information – numbers, letters, or words – can be found written on the back of a canvas, stretcher, or picture frame. Extremely useful, if one can decipher it.

The research process can be lengthy, rewarding, and exhilarating to the extreme when one is successful, and hopelessly frustrating when one is not. The proverbial brick wall is often encountered.

It requires patience, perseverance, and tenacity.

But not always.

Sometimes, as in the case of a Dunning Down Under, fortune is benevolent.

Establishing provenance was as easy as an email.

Auction houses typically protect the identity of their clients, and many consignors wish, for various reasons, to remain anonymous. Perfectly understood, that.

But it never hurts to ask.

To that end, an email to my contact at Leonard Joel posed a simple question. Would the auction house be willing to forward an inquiry to the consignor of the painting on behalf of the FRHS, asking for their assistance in documenting provenance?

The response: “Yes.”

And so, an email was dispatched and, as it turned out, quickly forwarded.

Within days, I had a response from the consignor:

“It was bequeathed to me by an elderly American friend who died two years ago. Please get in touch with me if you would like to know more about her and her family.”

Australians, as I said, are nice people.

Rhode Island to Down Under:

From the consignor – the quotes are hers – I learned the following:

The painting belonged to a Providence, Rhode Island, native who grew up in Barrington, Rhode Island; she was the daughter of a tennis instructor and a hospital matron. Following a private primary education, she entered Smith College and graduated in the early 1960s. After graduation, she was employed at The Providence Journal as a trainee journalist.

“In 1962, while covering the America’s Cup yachting races, she was recruited by Sir Frank Packer to work on his newspapers in Sydney, Australia. She did not live in the USA again – working variously in Sydney, [and, later] in Port Moresby, Papua, New Guinea,” where she taught in the English department of a university.

After her marriage to an Australian national, “she worked with her husband on his family’s vineyard, as a radio producer for the Australian Broadcasting Commission, and from the late 1980s onward … as Public Relations Director for the Melbourne Zoo.” She died in Australia in 2020.

The painting “was one of several items sent to Australia after her mother’s death.”

Question answered: That is how it got … there.

It is thought that the picture descended through her paternal family line. Research into that possibility will continue and new links may be added to the chain of provenance.

Serendipity:

I like the thought of things coming full circle. In the case of a Dunning Down Under, it surely did, and I am pleased to have played some part in it.

The consignor was pleased:

I didn’t keep the painting because I had other things by which to remember my friend. I’m an art historian with a particular taste in paintings and furniture and while I appreciate the quality of [the] still life, it wasn’t for me. I’m very pleased that it has found the best possible home – exactly the kind of outcome I’d hoped for.

It was exactly the result I had hoped for as well.

And so, it came to pass: 140 years after it was painted, the Dunning still life painting returned to Fall River.

I like to think that the Rhode Island native who had family heirlooms shipped to her home in Australia would also have been pleased.

To read more about Robert Spear Dunning and the painting, please visit our website here.