If nothing else, compliance with Center for Disease Control and Commonwealth of Massachusetts recommended protocols pertaining to the coronavirus pandemic has allowed for long postponed archival projects at the FRHS to be completed.

In this case: Work with Durfee Mills accident reports dating from the nineteen-teens to early twenties.

The reports were donated to the FRHS in 1988, having been stored for decades – along with heaps of other records, also given to the museum – in the attic of the old Durfee Mills office building on Pleasant Street; they were discovered during structural renovations.

The donor, a long-time FRHS member, benefactor, and a Fall River native with a great interest in local history, was also friendly with the then-owners of the Durfee Mills complex; when the records were discovered, he was given first dibs.

His initial visit to the attic prompted a telephone call to the FRHS and, as a result, I accompanied him the next day on a return visit. My first reaction: Not quite fit to print. The place was an absolute mess. Strewn everywhere were heaps of ledgers, file boxes of business letters – decades of them – pay receipts, work orders, and the like, all documenting two centuries of the day-to-day business transactions of one of Fall River’s most successful textile manufactories.

The whole was covered by a layer – striations, actually – of dust, dirt, droppings from various animal species, the occasional desiccated carcass – the origin of said droppings, some with remnants of feather or fur intact – and more grime than can be imagined. It was a disaster. But an archival treasure trove, really, when one came to terms with the initial shock of the place and looked beyond the obvious.

And was it ever hot.

And so, over the next few weeks, despite the heat and grime – no elevator, of course – several hundred volumes and scores of documents made their way into the FRHS collection.

Decades of storage under the eaves of a building that suffered deferred maintenance for many years furnished less-than-ideal survival conditions for paper, with temperatures fluctuating from extreme cold in the winter to heat in the summer, with corresponding changes in humidity, all exacerbated by a leaky roof.

In fact, it is remarkable that the records survived at all.

Peppered under the stacks was a plethora of buff-colored 4” x 9” envelopes that upon inspection were found to contain employee accident reports. Each envelope was typewritten with the employee’s name, position, and accident date, followed by “Home,” after which a date was entered in long hand – but not always – indicating when the employee left work, and the abbreviation, “Rtd.” for Returned to Duty, after which a date was always entered.

Fascinating material, no doubt, and important historically.

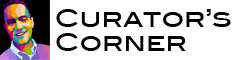

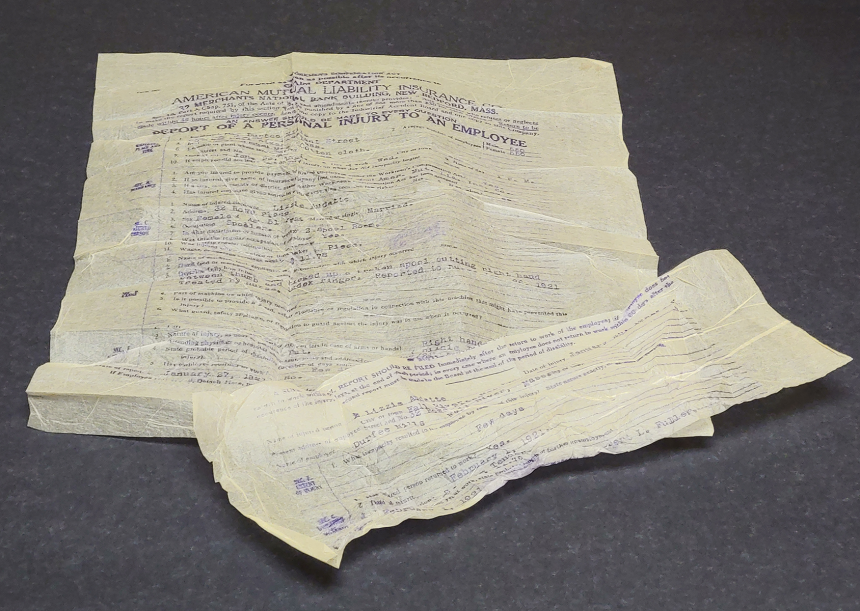

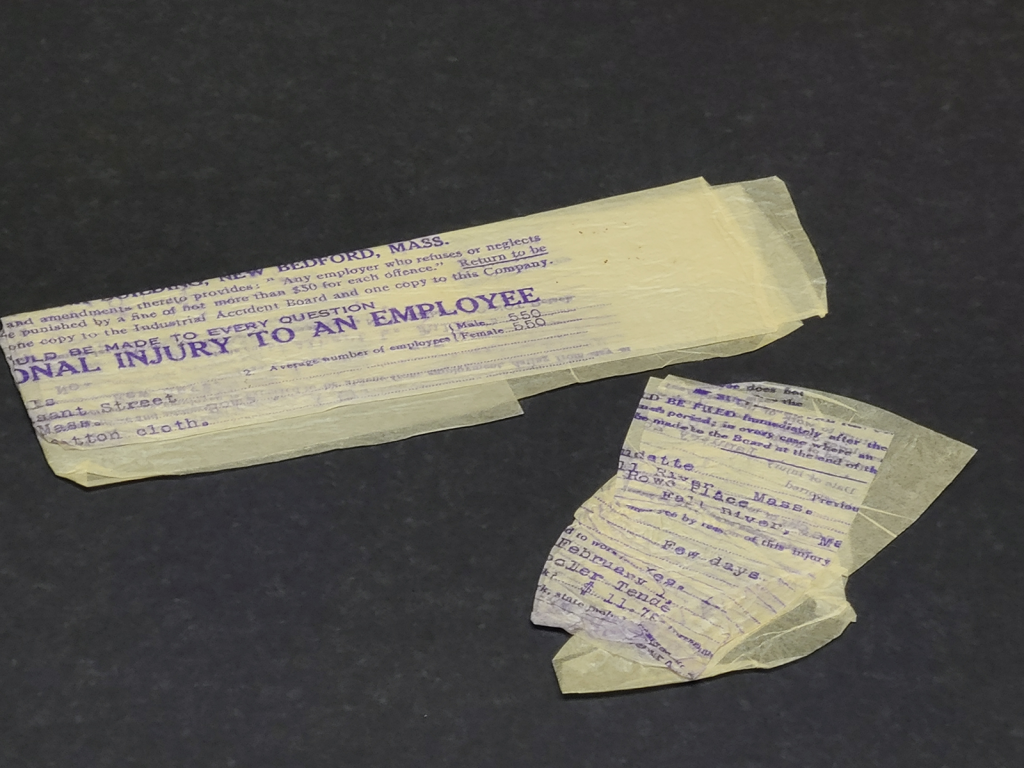

The vast majority of the envelopes contained four sheets, in the least, and often more, detailing the particulars of the accident and the eventual outcome. The information was recorded by the department overseer, the company nurse, and the office secretary, the latter dutifully filling out standardized insurance claim forms with all the particulars. Two onionskin paper copies of the forms were retained for the company files.

Statistical information gleaned from accident reports in Massachusetts factories was compiled by the state and is readily available to researchers, but this collection of records is particularly significant because it constitutes a dossier of each accident, from the day of the incident, through treatment, recovery and, in a few cases, permanent disability.

Particularly interesting are the details of the accident as relayed by the employee to the overseer, and the method of treatment – often refused – directly recorded by the attending nurse or relayed to her by the physician. Occupational risks were many and accidents frequent; injuries to hands and feet were the most regularly reported – fairly unpleasant stuff, to be sure.

The reports are particularly interesting to me because they hit close to home.

My paternal grandfather – a weaver at the Sagamore Manufacturing Company – lost the greater portion of a finger as a result of an industrial accident in the nineteen-teens, in his case, operating a loom. I was only seven years old when he died so my memories of him are sketchy, but by all accounts he was a very nice man and I have never heard a disparaging comment about him. He put up with much from his wife – she could be tough – his only child, who was my father, and his five grandchildren, of which I am the youngest.

As a boy, I recall sitting on his lap, spraying an a ample application of Lemon Pledge onto his bald head, and polishing it to a brilliant sheen with a dust rag – amazing, really, what furniture polish can (or could) do to scalp.

But the one thing I remember most distinctly about him was the stub on his right hand where a forefinger should have been – absolutely fascinating to a child. Where was it?

The Durfee Mills accident reports detail similar scenarios; many were the men, women, and children in Fall River permanently scarred as a result of their work. Wheels lost cogs, employees lost fingers, or worse – both were considered disposable commodities, easily replaced.

Fall River’s cemeteries are filled with the skeletal remains of its industrial workforce; how many are badged with a missing joint bone, I wonder?

There was a major issue with the accident reports, specifically with the onionskin copies: Decades of storage under the weight of ledgers and boxes of records, coupled with fluctuating temperature and humidity had tightly compacted the sheets, causing the coated onionskin paper to fuse together.

They were compressed very flat, some into fascinatingly irregular shapes with the printed and typewritten text scrambled, by virtue of contraction, into something akin to veining on extremely thin slivers of brittle marble. It was impossible to open them without causing irreparable damage.

Conservation – possible to undertake in-house – would take a considerable amount of time, something at a premium for the FRHS.

And so, in storage the reports remained – for thirty-two years.

Until the COVID-19 pandemic, that is.

Earlier in the year, when non-essential businesses were closed, the FRHS staff began working remotely; I was the only person in the museum building on a daily basis.

Amazing, how quiet the place is.

As such, I was able to accomplish a great deal, with social isolation allowing for long stretches of uninterrupted time to devote to a single, rather involved project.

The project?

Onionskin accident reports.

And so, as weeks morphed into months – I lost count of the hours – I carefully applied distilled steam to release the fused bond on onionskin insurance claims in 446 individual files, and with tweezers and scalpel coaxed the sheets open, after which they were weighted and flattened into their original form.

Finis!

My magnum opus of the textile mill record variety, if such a thing exists.

We are now in the process of cataloguing the reports and storing them in acid-free materials.

And who knows?

Perhaps, one day, Sagamore accident reports will be discovered, revealing the details of my paternal grandfather’s lost digit.