Sometimes, a seemingly mindless act – in this case a Google search – sets into motion a series of events that bring to fruition something long hoped for … the reunification of a family, of sorts, an important museum acquisition realized, and the culmination of a long sought quest.

The pitfalls: Patience – decades of it – and rather a bit of angst along the way.

It was the evening of Monday, September 3rd, 2018, and I have no idea what prompted the Google search at that particular moment.

“Marie Merkel-Heine.”

The resulting image caused my heart to race, and the accompanying text, read as the result of a click, confirmed my suspicion – and my fear – hitting me in the pit of my stomach.

I was stunned, and to be perfectly honest, nearly sickened. No exaggeration, that.

Could this be possible? Was it actually as it appeared?

Worse yet: How did I miss this?

And unfortunately, it proved all too true.

For me, it had started in 1983.

But in actuality it began in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1881.

The scenario: A visibly ill man, nearly emaciated and aged beyond his years, arranged for a series of portraits on porcelain – painted not from life, but from photographs – to depict members of his immediate and extended family; he had only weeks to live and would never see the portraits finished.

The man: Fall River industrialist David Anthony Brayton Sr. (1824-1881).

The artist: Marie Merkel-Heine.

Little more than a century later – in 1983 to be exact – I saw one portrait from that commission for the first time, and one year later I saw another, both apparently the work of the same artist.

Were there more?

A commission of some sort?

Several years later, I saw my third portrait, and within months, the fourth; both dated 1881 and, once again, the work of the same artist.

Suspicion confirmed … there must have been a commission, and apparently, a large one.

The common denominator: Descent in the immediate or extended family of David A. Brayton Sr.

Thus began a quest that would take over three decades to realize, culminating with a Google search on Monday, September 3rd, 2018.

And so it began:

Segway back to 1983.

There was an astonishing lack of photographic material in the FRHS collection documenting the history of the mansion – formerly the residence of David A. Brayton Sr. – that now houses the museum. Ideally, we were looking for interior views of the building, to be used as aids in future restoration, interpretation, or documenting provenance.

In the hopes of remedying that, I began by contacting the Brayton descendants who resided in the greater Fall River area – most were in some way connected to the FRHS – to inquire about photographic material in their private collections.

David A. Brayton Sr. was the father of five children – only two, Nannie and Dana, married and had children, so the search was confined to their offspring. The senior members of Dana’s line had maintained membership in the FRHS; as such, they were easy to contact. An inquiry for photographs – specifically, interior images of the building – turned up nothing.

As one would suspect, there was a plethora of portrait photographs, “Brownie” snap-shots, and travel albums – they were very willing to share those – but nothing to document the structure.

Strike one.

But what of Nannie’s descendants?

Following the death of her first husband, Norman Easton Borden Sr. (1850-1884), and her remarriage in 1892, to Henry Wayland Peabody (1838-1908), Nannie and her two children left Fall River, dividing their time between residences in Salem and Beverly, Massachusetts.

The quest: To find the descendants of Nannie Jenckes (Brayton) Borden Peabody (1853-1905), who had not maintained contact with the FRHS.

And find them I did, although it took rather a bit longer than it would today, this before the ease of the internet and on-line ancestry sites.

Mostly, it was done by USPS, followed up via telephone.

The response to a letter sent to one of Nannie’s grandsons, then living in Vermont, was very much the same as those from his cousins: He had no photographs of the family residence in Fall River, but he did have several of his ancestors.

Strike two.

But not quite.

You see, he did have something rather special. A beautifully rendered portrait on porcelain of his grandmother, Nannie. It was painted in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1881 – though I did not know that at the time.

I did not see the actual piece– I would have to wait thirty-five years for that – but Nannie’s grandson described it to me via telephone and followed up by sending a not-very-good photograph of the instamatic-type; still, even with a lousy photograph, it was clear that the portrait was special.

In the course of conversation he said: “Someday, it should probably go to the historical society.”

And someday it would.

The next year: Summer, 1984.

A descendant of one of the brothers of David A. Brayton Sr. contacted the FRHS with the offer of a donation of several family items, among them a portrait: “Painted on ivory [of] my Grandfather, Hezekiah A. Brayton.”

The donor, a fascinating “Miss” of the old school, was immensely proud of her prominent Fall River ancestry – at times rather odd, and prone to eccentricities, she was set in her ways, and best not trifled with, especially so when her mind was made up.

Offer gratefully accepted.

The portrait of Hezekiah Anthony Brayton (1835-1908) was lovely, beautifully painted and of exceptional quality, and though unsigned, it was clearly the work of a very talented artist. It was presented in its original gilt frame, which bore the label of Williams & Everett, a 19th century Boston, Massachusetts, framer and gilder, favored by an elite clientele.

But it was not painted on ivory – quite the contrary: It was painted on an exceptional quality Königlische Porzellan Manufaktur (K.P.M.) porcelain plaque, and on the reverse was its original paper label from the Merkel-Heine Porcelain Decorating Studio, Wiesbaden, Germany.

Yet our fascinating “Miss” of the old school was certain it was painted on ivory. She had always been told by the family that it was painted on ivory. Thus she knew it was painted on ivory.

A wise man knows that some battles are best not fought: At times, it is best to smile, and retreat.

“Yes, Miss … of course it was painted on ivory.”

Enough said.

But it was not – it was painted on K.P.M. porcelain and bore a striking resemblance to the portrait of Hezekiah’s niece, Nannie, depicted in the not-so-good photograph that had been sent to me the year before.

A comparison of the two – the actual portrait of Hezekiah and the photograph of Nannie’s portrait – confirmed the fact: They were clearly the work of the same hand, and appeared identical in size.

Interesting.

My immediate thought: Were there additional portraits, perhaps commissioned by a family member?

It would be several years more before my suspicion was confirmed.

In early October, 1991, I first met a woman who was a direct descendant of David A. Brayton Sr. and over the subsequent years we became good friends – very good friends, I would say.

I spent considerable time visiting her at her beloved home in Little Compton, Rhode Island – specifically Sakonnet. It was a rambling house that was once two, joined together in the early twentieth-century by its then owner, and was surrounded by acres of open lawn and fields. There was a garden glade with a winding path at the end of which was a granite mill stone, cleverly repurposed as a table top and inset with 1920s coins dating its construction, there were substantial outbuildings of various sorts – a barn, a guesthouse, and the like – and the whole was bordered with ancient liken-and-moss-covered fieldstone walls; the scent and sound of the sea was ever-present.

Heaven on earth in her opinion, and in that she was correct – the place held a spectacular charm and I relished my visits; she had spent most of her childhood there, and eventually came to possess it as her summer home. Later, it was her permanent residence.

I had many happy times there, and though I will likely never set foot on the place again – she died several years ago, and the property has since been sold – I still smile every time I drive by, pine for times past, and think of its former mistress: A great lady, fondly remembered and very much-missed.

Interested in her family history, she lived with generations of paternal and maternal family pieces, some used on a daily basis and heaps of others, not, and therefore stored in every conceivable space – practical or not – in her very large home, or in the guesthouse, or in the barn, or in one of several outbuildings.

Over the ensuing years I came to know the house – and the lady of the house – well, and many things made their way back to the FRHS, “back home” as she often put it. She was delighted to have her family pieces displayed and cared for and knew that her father – “Daddy” – would have approved.

It was while visiting the FRHS in 1992 that she commented on the portrait of Hezekiah A. Brayton, then hanging in the parlor; a conversation ensued, during which I mentioned my suspicion that there may have been others.

Her reply:

“I have one of those. Of Elizabeth H. Brayton, Aunt Liz. Do you want it?”

My answer:

“Yes.”

Elizabeth Hitchcock Brayton (1865-1935), by the way, was the youngest daughter of David Anthony Brayton Sr., and the younger sister of Nannie Jenckes (Brayton) Borden Peabody, whose portrait I had seen in a photograph nine years before.

Sense a pattern here?

Shortly thereafter, I drove to Little Compton. On her kitchen table, was a package, tied with discolored twine and wrapped in brittle craft-style paper, peppered with ages of dust – it was torn a bit, likely decades before to see what it protected.

Inscribed on the paper in ink in a very neat hand that I later came to recognize as that of Miss Jane Davis Howland (1876-1955) was the name “Elizabeth Hitchcock Brayton”; Miss Howland had been hired companion to Miss Elizabeth H. Brayton and later served as executrix of her estate.

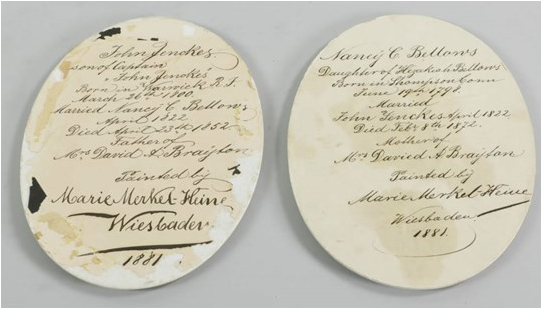

As promised, in it was a portrait painted on porcelain of Elizabeth, identical in style and size to the portraits of her sister, Nannie, and her uncle, Hezekiah. Best of all, on the reverse of Elizabeth’s portrait was an inscription, with her detailed biographical information, an artist’s signature, date, and location: “Marie Merkel-Heine, Wiesbaden, Prussia, 1881.”

Finally, an artist, a date, and a location.

The portrait was still in its original gilt frame, on the reverse of which was affixed the label of Williams & Everett of Boston – the same shop that framed the portrait of Elizabeth’s uncle, Hezekiah.

And then Fortuna smiled: Within the hour, in walked the brother of the house, also a Little Compton resident and a giant of a man whom I had the pleasure of coming to know well and call a friend – a privilege, really. Until I breathe my last – providing that I still have my faculties – I will never forget our final conversation, having been summoned by him to his hospital room for a final farewell.

When he saw the portrait on his sister’s kitchen table he indicated, almost as an aside, that he also had one of those, a portrait of Elizabeth’s brother, Dana Dwight Brayton (1869-1927), the youngest child of David A. Brayton Sr. He was not certain exactly where it was, but he knew he had one, “somewhere” in his house, not so very far away.

Interest piqued.

An explanation of the significance of Elizabeth’s – and, accordingly, Dana’s – portrait followed.

His immediate question:

“Do you want it?”

My answer:

“Yes. Thank you.”

A few months later, in 1993, the portrait was located; I went to Little Compton, and in short order another Brayton portrait made its way back to the FRHS. As suspected, on the reverse was detailed biographical information about the subject, the artist’s signature, date, and location: “Marie Merkel-Heine, Wiesbaden, 1881.”

This portrait was also in its original gilt frame, and also bore the label of Williams & Everett of Boston – the same shop that framed the portraits of Dana’s sister, Elizabeth, and uncle, Hezekiah.

Suspicion confirmed: There clearly must have been a series of portraits commissioned and I suspected when and by whom: David A. Brayton Sr. left Fall River in 1880 on an extended trip abroad in search of a cure for his declining health and was in Wiesbaden, Germany – then Prussia – in 1881, “taking the waters,” hailed for their curative properties.

His attempt was unsuccessful: He died in London, England, in August, 1881.

Surprisingly, attempts to uncover information about the artist proved unsuccessful – this woman of immense talent proved elusive, with relatively nothing recorded in sources available at the time.

Fast-forward: The next year, 1994.

And then there was the box.

It was sitting on a shelf – one of several shelves – that ran the length of the west wall of the attic in the north wing of the house in Little Compton. It was a rambling attic, with recesses, and eaves at odd angles, and built-ins, and cedar closets, all stuffed to overflowing with heaps of treasures – or not – the by-product of several generations of well-heeled family homes all stuffed into one, and large though it was, it was filled to nearly bursting.

The accumulation can, perhaps, be likened to striations in rock, with layers built up over decades – the deeper into the eaves one penetrated, the older the material, i.e. the last house cleared out was simply packed in front of the previous one, hence the layers. And there were several.

A visit was like a treasure hunt, and the lady of the house reveled in it as much as I did.

It was dusty and gritty, often very hot – or cold, depending on the season – and stuffy beyond measure, with evidence of finely chewed paper habitually accompanied by the distinct odor of long-dead mice – one hoped.

But those inconveniences paled in comparison to the fun – the thrill of the hunt, really.

The shelves on the west wall of the attic in the north wing of the house were littered with an odd assortment of things, evident when one was able to ferret a way in: There were cased glass fluid lamp reservoirs designed to fit into candlesticks in the days when fluid lamps surpassed candlesticks as a “modern” form of lighting; a Tiffany studios Zodiac pattern picture frame; photographs in various stages of preservation – or decay – framed, or not; sports equipment – modern or not quite; old lampshades that should have been thrown away; porcelain and glassware from centuries past; plastic flowers; badly tarnished silver serving pieces and trophy cups; decorations for every conceivable holiday; candles, misshapen by heat; old shoes; hats in myriad styles … and, well … stuff.

Heaps of it, with more piled in … always room for more, or so it seemed.

It was an incongruous mix, overwhelming to the timid, but to me intriguing beyond measure, a veritable Aladdin’s cave of Fall River and one family’s history … best of all, I was Aladdin, and the lady of the house a beneficent genie, delighted to have her family pieces identified, appreciated, and, in many cases, sent “home” to the FRHS.

And so it was that one afternoon, after lunch, came a romp in the attic and a eureka moment to best other eureka moments, at least in my estimation.

I saw a box on one of the shelves on the west wall of the attic in the north wing of the house.

It was a small box, really a well-constructed wood packing crate, covered in dust and likely untouched for decades – intriguing, old wooden boxes, dusty and long unopened.

Prying open the lid was somewhat of a chore, but pry it off I did, revealing a pad of excelsior, dry, to be sure, but as pristine as the day it was packed. Lifting the padding, I saw a fitted interior, with several narrow slots, each stuffed, in turn, with more excelsior – my heart began racing because I began to suspect that which soon came to pass.

Some slots were empty, but in four a white band could be detected, evidence of the edge of porcelain – could it be a porcelain plaque? A grasp of the edge of one piece between my thumb and forefinger confirmed evidence of my suspicion – unframed porcelain plaques.

Lifting the first plaque I saw a face, a familiar face of a middle-aged woman, and the next, a man, aged beyond his years, and then another, a younger man, and the next, another man, younger still, the last three as familiar to me as the first.

The subjects: David Anthony Brayton Sr., his wife, née Nancy Roxanna Jenckes (1827-1909); their eldest son, David Anthony Brayton Jr. (1855-1913); and their second son, John Jenckes Brayton (1859-1915).

An epiphany and excitement difficult to restrain, but, hell, why attempt to curtail it at all – I had been waiting years for this, and my senses thrilled with the realization that before me was that which I suspected existed – had hoped existed – for several years.

On the reverse of each, in keeping with the other portraits in the series, was detailed biographical information pertinent to the subject, the artist’s signature, date, and location: “Marie Merkel-Heine, Wiesbaden, 1881.”

Yes, indeed, there had been an 1881 commission for a series of portraits, and in my hands were the four examples that completed the set depicting the immediate family of David A. Brayton Sr.; for some reason, they had never been framed.

The lady of the house, my companion exploring that dusty attic, was delighted with the discovery – not so much as me, to be sure, but nearly so – having never seen them before in her many years in that house. Her immediate response of course, was that they had to go “home” to the FRHS, and I did not hesitate to accept.

And so it was that by 1994 the FRHS held in its permanent collection six of the portraits from the 1881 Brayton commission, and was able to reunite the family members – sans one – that had resided in the building that now houses the museum: David A. Brayton Sr.; his wife, Nancy; his sons, David, John, and Dana; and his daughter, Elizabeth.

As an added bonus: The portrait of David’s younger brother, Hezekiah that had been donated to the museum by the fascinating “Miss” of the old school in 1984.

But the reunification of the family was not yet complete: David A. Brayton’s eldest daughter, Nannie, was still, apparently, in Vermont.

It would be twenty-four more years before the final reunification of the portraits of the immediate family of David A Brayton took place.

Over the ensuing years, I became aware of three additional portraits of Brayton family members, depicting: Israel Brayton (1792-1866) and his wife, née Keziah Anthony (1792-1880), the parents of David A. Brayton Sr.; and Israel Perry Brayton (1829-1878), one of David’s younger brothers.

These three examples descended in the family of the latter – a family that maintained a close association with the FRHS – and were all undoubtedly part of the Brayton commission: The work of Marie Merkel-Heine, they were painted in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1881, and had been framed by the Boston shop of Williams & Everett.

Undisputed provenance on the portraits came in the form of a document donated to the FRHS as part of a large collection of manuscripts pertaining to the lives of David A. Brayton Sr. and his children. It was a twenty-page manuscript headed “MEMORANDUM,” typewritten on legal sized onionskin paper, dated 1930 and twice amended – in 1932 and 1934 – being the memorandum to the will of Miss Elizabeth Hitchcock Brayton, the last resident of the FRHS.

It is a fascinating document that was left for her executrix, and laid out, in minute detail, Miss Brayton’s exacting wishes for the dispersal of her property not bequeathed specifically by will; it has proved instrumental in documenting the provenance of many Brayton family pieces.

Among the myriad bequests listed were the portraits painted by Marie Merkel-Heine.

Left to the father of my Little Compton lady:

“All portraits of my parents and brothers painted on porcelain.”

These included the four unframed portraits that I had found in the box in the attic in 1994 – David A. Brayton Sr., his wife, Nancy, and his sons, David, and John – and the framed portrait of his youngest son, Dana Dwight Brayton.

And left to my Little Compton lady, who was only seven years old at the time:

“Framed porcelain picture of E.H.B. This was painted in Wiesbaden, Germany, and the birth date on the back should be Sept. 16, 1865, instead of 1866, as it now stands.”

This referred to the framed portrait of Miss Elizabeth Hitchcock Brayton that I first saw on a kitchen table in Little Compton in 1992.

But the portrait of Nannie still eluded us.

Until my Google search on the evening of Monday, September 3rd, 2018.

As I mentioned at the beginning of what has become a rather lengthy posting, the image – actually images – that appeared resulted in rather a bit of panic on my part, especially so after reading the accompanying text.

Did I say I panicked?

Believe me, it was far worse than that.

Much worse.

What I read was a lot listing from Kaminski Auctions, in Beverly, Massachusetts:

Lot 9011:

19th Century German Family Portraits on Porcelain:

Family Portraits on porcelain by Marie Merkel-Heine of Wiesbaden, Germany, 1881, framed portraits of Nannie Brayton Borden and Norman Easton Borden (husband and wife), plaques of John Jenckes and Nancy C. Bellows (wife of John Jenckes), 7” x 5 ¾” plaques, 11 ¾” x 9 ¾” frame.

Minimum Bid: $200.00

Final Bid: $225.00

Estimate: $400.00 – $800.00

Number of Bids: 3

So, there you have it.

Nannie’s portrait, the first one from the Brayton commission that I saw in 1983, together with three additional that I did not know existed, were sold at auction on April 7, 2018, and a befuddled and anxious I was reading the listing exactly 149 days later, on Monday evening, September 3, 2018.

A thirty-five year quest, brought to a close by an auctioneer’s gavel.

The portraits had been sold and were lost to the FRHS.

Angst … and then some.

So, I wallowed in self-pity for a while … cursed like many a sailor … regrouped … recovered my senses and formulated a strategy.

Tuesday, September 4th:

Immediately call Kaminski Auctions, explain plight, and ask – beg, if necessary – that they forward a message to the purchaser explaining situation. Fortunately, the good people at Kaminski were very accommodating – to the extreme, actually – and immediately offered to help in any way possible.

Compose message to purchaser, asking – beg again, if necessary – that they please consider reselling the portraits to the FRHS.

Send message to Kaminski’s, and wait.

Wednesday, September 5th:

Check email and telephone – no messages. Could not wait any longer – it was less than twenty-four hours but was driving me mad.

Call Kaminski to confirm that they received my email sent the day before.

Answer in the affirmative: Email received and forwarded.

Thursday, September 6th:

Immediately check telephone messages and emails.

Nothing.

Check throughout morning and into early afternoon.

Nothing.

Thought to self: This does not bode well … why are they not calling?

Finally: red light on telephone indicated a new message.

Play message:

“Hello, this is Angela …” calling from Ashby, Massachusetts.

Relief beyond measure.

Return call. Yes, the antique dealer purchaser still had the portraits and was willing to resell them to the FRHS for $750, which included the original purchase price, auction commission, and shipping, in addition to a small profit. They had purchased them for resale, had never unpacked them, and sort of forgot about them – until my inquiry.

Relief again: Fortunately, there is $750 available in the Acquisitions Fund.

In short order: Check sent, and portraits picked up shortly thereafter by two FRHS volunteers.

I have since found out that the portraits were consigned to Kaminski by a Borden family member of the next generation who had absolutely no idea that I had ever inquired about family material, or that the FRHS was interested in the pieces. If they had known, the pieces would have made their way to the FRHS by a far more direct route.

So, what do we now know about the portraits?

In 1881, David A. Brayton Sr. did, indeed, commission a series of twelve portraits depicting members of his family, and at least two additional, depicting two of his younger brothers.

The majority of the portraits, framed or unframed, remained in the Brayton residence – now home to the FRHS – until 1935 when they were disbursed by a memorandum to a will; additional portraits from the 1881 commission descended in the families of the individuals depicted in them.

In 1983, a younger me began a quest to reunite the portraits of the immediate family members of David A. Brayton Sr., blissfully ignorant with the naiveté of youth that it would be a thirty-five-year pursuit.

Nor did I know at the onset that the fates would toy with me along the way, in the end taking away before giving back, but ultimately deciding on benevolence, thus allowing me to bring the damn thing to fruition.

A satisfying journey – though at times, rather a bit fretful.

The next steps:

Research: Who was Marie Merkel-Heine?

And a thought: Were others of David A. Brayton’s siblings painted as well?

Perhaps when he commissioned his immediate family, he contacted all of his brothers or sisters, asking if any were interested in ordering portraits – this would explain the existence of the portraits of his two younger brothers, Israel and Hezekiah.

Next up: Inquire with other Brayton family descendants, enlisting the assistance of friends who are family members.

Interesting thought.

In addition to the pieces held in the permanent collection of the FRHS, there are three on temporary loan from a private family collection.

So, if you have made it this far and are still in the least bit interested, these fourteen portraits are currently on display at the FRHS and will remain on exhibit until December 30, 2018.

For the FRHS they are beautiful works of art of museum quality, created by a relatively unknown lady painter of extraordinary ability.

For me, they represent the end of a thirty-five year quest.

Finis!

Very rewarding, that.