It is surprising what can accumulate between the pages and along the inside spine of an old ledger over the decades – dust, soot from coal or wood fires, long-dead insects (ideally), and the like. But quite often, the material found there is contemporary to the volume, in situ since ink was put to paper.

One important step in the preparation of archival material for cataloguing and shelving is cleaning; often unnoticed, it is integral to the process, and imperative for ensuring the preservation of ephemerous materials. Using a variety of methods – brushing, vacuuming, dry cleaning pads – the intent is to remove any harmful debris from the surface of the paper and binding.

Case in point:

A collection of ten ledgers from Cook Borden & Company, Fall River’s leading lumber merchant for well over a century. Donated to the FRHS by a direct descendant in the male line, the volumes span the years 1832-1879, and have survived in remarkable condition.

In preparing the collection for recataloguing and shelving, it was discovered that the majority of the volumes, dating to the 1830s and 1840s, contained significant amounts of writing sand that had been liberally sprinkled on the pages by some long-dead clerk – a common practice of the day – to absorb wet ink and prevent smudging.

Blotting, or bibulous, paper had been invented by the late 18thcentury, but it was not commonly used, and was not introduced in the United States until the 1840s. Before that time, so-called “writing sand” was the best method of absorbing excess ink, applied by sprinkling from a “sander,” or shaker, a common desk accessory similar to a salt shaker; made from a variety of materials, they often had a concave top – excess sand would fall back into the shaker, eliminating waste.

The material used for blotting varied: very fine sand, often mixed with pumice or ground cuttlefish bone; pounce, made from ground cuttlefish bone; or gum sandarac, a resin derived from the Tetraclinis asticulate, an evergreen in the cypress family, dried and ground into a powder.

Regardless its origin, traces of writing sand residue often remained on the surface of the paper it was applied to – in short, it was messy.

The inkstand depicted in the photograph – of English manufacture dating to the 1840s – is from the FRHS collection; the “sander” can be seen at the right.

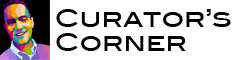

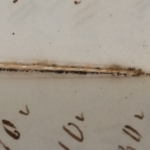

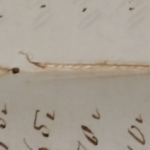

In the case of the Cook Borden ledgers, the surface of many pages felt gritty to the touch – evidence of excess writing sand that clumped up and adhered to ink – and substantial amounts had also settled between the pages along the inside spine.

Not a good thing, that.

The material is abrasive and settles deeper into the stitched and glued spine every time the volume is opened and the pages leaved through – much like sand paper, it wears and grinds, destroying the fragile paper, stitching, and binding material.

The remedy to the problem – remove it.

The process is time consuming, but it is often necessary to go to great lengths to safeguard archival materials; in this instance, approximately 3470 pages were individually cleaned.

These images depict the same pages before, and after, the removal of the gritty writing sand – the difference is rather dramatic.

Speaks for itself, does it not?